Grades Reconsidered

Grades Reconsidered

"What you measure affects what you do." — Joseph Stiglitz

"In this class I never had to worry about my grades. I knew that if I did all the work that was available to me (and there was always more than enough to keep me busy) and tried my best, the grades would just work out. But what was more important was that I actually learned a lot." — Lauren C., student

"Learning for a grade is seriously pointless." —Mady M., student

“What do I need to do to get an A?” How often have you heard a variation of that theme? Does your heart sink when you hear it? It should.

Academic materialism is an unmistakeable symptom of doing school: the desire to be “successful” in school by accumulating the best grades. For the student who asks this question, learning has become a fringe benefit of doing school efficiently. She is in the thrall of grades, and as a result, she is missing out on the experience of self-directed learning.

Most of us take for granted that grades are a necessary and important part of school. Certainly they are not going away anytime soon, since they are an integral part of a much larger system (college admissions spring to mind). But more than any other factor, grades push students into the bad habits of doing school. No one intends this to happen, but it is a ubiquitous problem in our educational system nonetheless.

Successful students often identify with their grade status — I have seen students weep bitterly at getting less than an A on a test — while the corresponding damage that low grades do to the identities of unsuccessful students is incalculable.

One of the central goals of our new paradigm is to break the spell of grades by redefining their purpose. Rather than being a system of rewards and punishments, an external motivator, or a way to sort students along a bell curve, grades can become an important and useful part of the learning process.

This change can be accomplished in part by creating a classroom culture that focuses relentlessly on self-directed learning and deemphasizes the importance of grades. But structural changes are also necessary. This chapter will explore three broad strategies for redefining the meaning of grades: Disentangling feedback from grades, having students self-evaluate their work, and participating in grade conferences with students.

In order to know why we need to implement these strategies, however, it is important first to carefully consider what functions grades currently serve, what meaning they have, and the inadvertent damage they can do.

9.1 The Dark Side of Grades

9.1 The Dark Side of Grades

"In environments where extrinsic rewards are most salient, many people work only to the point that triggers the reward— and no further. So if students get a prize for reading three books, many won’t pick up a fourth, let alone embark on a lifetime of reading." — Daniel Pink

"Before taking this class the only thing that was important to me was getting an A. But, after I learned more about your teaching philosophy, I realized how stupid that was. If I only worried about getting a good grade I could miss out on so much valuable information. Instead, if I concentrated on learning the material, I found that I could absorb the knowledge and do well at the same time." —Kelsey C, student

Grades externalize and distort student motivation.

One of the central tenets of doing school is that academic success means getting good grades, as opposed to experiencing genuine, meaningful learning. Grades become valuable for their own sake, and a student’s motivation is altered, sometimes profoundly, and often unconsciously. She may be driven to cut corners or even cheat to accomplish the goal of getting good grades. Whether she is achieving the course’s learning goals is often irrelevant to her.

If you doubt that, ask yourself this question: “If there were no grades, would your students work as hard or learn as much?” If you’re like most teachers, the answer is almost certainly “no”. And your students probably agree.

Even for academically successful students, grades have a corrosive effect on motivation. Academic materialism can cause “good” students (and their parents) to be confused about what matters in school. It can foster priorities that drown out a student’s desire to learn for the sake of sheer curiosity or the urge to know something new.

Grades embody a power structure that distorts the relationship between teacher and student.

Grading is commonly (though often unconsciously) used by teachers as a means of exerting power over students. In its most overt form, grades can be used to reward and punish behavior. Even when grades are used more subtly, the teacher is still “giving” grades to the student. We say that the student “earns” points; what we mean by that is that points are a reward for successfully doing what the teacher has asked the student to do.

The obvious downside to teachers doling out grades is that it externalizes the motivation to learn. A less obvious downside, however, is that it continuously and ubiquitously enforces a sense of powerlessness in students. We don’t often speak of the power structure in a classroom, but that doesn’t mean that there isn’t one. It is the sea in which we swim.

Any hierarchy of power has real human consequences. Grades can be used to punish students who are, say, disobedient. The use (and abuse) of this power contributes to an adversarial relationship between teacher and students.

Grades are a limited, simplistic form of feedback.

It goes without saying that feedback is a critically important part of the learning process. As we have seen, feedback gives the student the information she needs to make decisions about what to do next, what still needs to be learned, and whether she is ready to move on to the next topic. Feedback can come from many sources, including the teacher, fellow students, parents, or even a computer.

Grades, in the form of a number or a letter, are a sterile and not very informative form of feedback. A student doesn’t really need to know that she only got 73.5% of the answers right to know that she hasn’t mastered the material yet and has more work to do. To be meaningful, feedback must be much more nuanced and personal. Useful feedback informs the student of the specific mistakes she made, includes a discussion of what misunderstanding caused those mistakes, and provides a direction to remediate the misunderstandings. Grades, in and of themselves, are simply too crude a tool to do that essential work.

Grades are an ineffective means of communication.

Grades are often considered an important mechanism for communicating with parents and others about a student’s level of academic success. For the reasons listed above, it should be clear that grades by themselves aren’t a very sophisticated way to do that. A poor quarter grade may be due to low test scores, which may due to too much incomplete homework, which may be due to a drop in motivation, which may have to do with the student’s social life or sleep deprivation or any one of a number of psychological or physical problems. Sending a C- home doesn’t inform the parent of what the problem is in a subtle enough way to be truly useful.

Grades are arbitrary and subjective.

In basketball, a goal is worth two points unless it is shot from a specific distance from the rim, in which case it is worth three. These are the rules of the game. We know that someone made up those rules and we accept that it is an arbitrary definition. Grades are similar. The difference between a B- and a C+ is that one is a little above 80% correct, and the other a little below. Clearly, this is as subjective as the number of points a basket is worth, but we pretend that in the case of grades that we are talking about an objective reality.

When you create a grading system, you set a value on certain characteristics, like neatness or writing all the steps in a proof. Another teacher may start with a different set of priorities and come up with a different grading scheme altogether. There is no right or wrong about this, and when we act as though there is, we undermine our students’ belief in the authenticity of the grading process.

Grades are self-fulfilling prophecies.

People used to believe in medicine men or witch doctors who could heal or condemn with a curse. Modern, educated people dismiss these practices as mere superstition, but even today, words have real consequences, particularly when spoken by people with power. The link between belief and health, for instance, is unquestionably a real factor in the effectiveness of medicine. When a doctor declares that a condition is terminal, this often condemns the patient to a state of hopelessness which can have a profound effect on the body’s ability to recover.

What does it mean to be a “C student” or an “honors student”? The link between belief and the capacity to learn is as profound and mysterious as the link between belief and physical health. A “D+” is a voodoo curse, and not just for the student. When a teacher sees a student as a failure, her actions toward the student are shaped by that belief. It’s not healthy for anyone, and it is one of the most serious impediments to learning for many students.

Hopelessness is self-fulfilling, and failing grades induce hopelessness.

Grades sort students into better and worse learners.

By definition, our current use of grades requires some significant number of students to be unsuccessful academically. We profess that we want everyone to be successful, but what would really happen if everyone got A’s? Wouldn’t we have to “dumb down” the curriculum to accomplish this? How would colleges be able to select the “right” students? Most of us can’t imagine not sorting students by academic success, so when we say that we want all students to succeed, we usually mean that we want to see fewer D’s and F’s.

Grades make it difficult to imagine a learning environment where everyone is truly successful. They condemn teachers and students alike into becoming cogs in a sorting machine.

Grades distort a teacher’s priorities.

For starters, every hour spent grading is an hour that isn’t going towards some other activity that might be more useful for students (say, developing a new lab activity or preparing a more sophisticated lesson plan, or even getting some much-needed sleep). Furthermore, the inevitable struggles over points, particularly with “good” students, places the teacher in a role of mean-spirited withholding and creates power struggles where none need to exist. It is frustrating when you want to help a student understand what she got wrong on a test and instead you find yourself arguing over points. It forces both you and your student to focus attention on something which is much smaller and more superficial than whether the student has mastered the material.

Grades interfere with student-teacher working relationships.

Points invariably create a distance between teacher and student. When we are arguing about how many points something is worth, we are no longer on the same side, with the same goals. The adversarial posture that students adopt about how many points they should receive undermines the healthy working relationship that is based on mutual trust and respect. Conversations about learning are replaced with legalistic wrangling over points.

Minimizing the corrosive effects described in the sections above requires rethinking the meaning of grades. Here are some ways to reconsider their function.

9.2 Exploring the Meaning of Grades

9.2 Exploring the Meaning of Grades

When properly designed, grades can be a powerful tool, shifting student beliefs and motivation in a positive direction. This requires rethinking the meaning and purpose of grades.

Grades express values.

Whether we intend to or not, any grading system is communicating what we think is important. This can lead to unwanted consequences (such as rewarding behavior like grade-grubbing), but also provides an opportunity. If you value a student’s self-directedness or perseverance, for example, it is possible to create a grading scheme that rewards such behavior. What is needed is clarity about the most important aspects of a student’s experiences in your classroom — clarity about what is it that they should know and be able to do, as always, but also about who they should become. Grading schemes should be planned backwards from that perspective.

Consistency is not the same as fairness.

How can we define fairness when each student’s experience of learning is unique? We can make grades consistent and always follow the rules, obeying the letter of the law (no pun intended). But something is lost when we do that. The individualistic nature of every student working through the learning process in her own way requires us to pay attention to what success looks like on a case-by-case basis.

Giving students a voice.

A prerequisite for fair grades is a consensus about what is valued, what is being represented by the grade. The teacher and the student need to agree that the grade is meaningful and appropriate, which, in turn, requires giving students a voice in the grading process. The most direct means of accomplishing this comes through student self-evaluation, which is described in detail below.

Giving students a say in their grades flies in the face of most classroom practice. But if you believe in the validity of the grading scheme you are using and you trust yourself as a teacher to be honest with your students, then an evaluation in which you and the student agree is doable. If students have been self-evaluating their work, there will generally be little or no disagreement about what a fair grade is.

Grade conferences are another important mechanism for having meaningful conversations with students. Carefully defining the students’ role in the process of generating report card grades allows them to have a say without compromising the standards that the grades represent. It also creates opportunities for boosting student self-awareness and self-directedness. In my experience, students have agreed, almost without exception, that this approach to defining report card grades makes more sense and is fairer than many traditional schemes. Grade conferences will also be explored in detail below.

Points and the question of precision.

The use of points allows grades to be calculated to a high level of precision, but precision is not the same thing as accuracy. Throwing darts in a pattern like the one below shows how something can be precise but inaccurate.

Precision is not the same as relevancy, either. A prediction of 74.8% chance of rain is 0% relevant if it doesn’t rain and 100% if it does.

Similarly, being precise is not the same as being meaningful. The percentage of letters on every page of this chapter that are “g’s” can be calculated to 8 decimal places, but that doesn’t make it significant.

The problem is this: points are easily quantifiable, but learning is not. What does it mean that a student has an 82.6% average score on her tests this quarter? Has she learned 82.6% of the material? Is she completely wrong about 17.4%? The apparent precision of grades distorts the “fuzziness” of how human beings learn. When we use points, we run the risk of confusing the very simple, even crude quantification of grades with the infinitely complex and fluid landscape of the learning process.

This confusion has real and counterproductive consequences. Points formalize grades and make them “official”, which reduces the ability of teachers to talk candidly with students about learning. It makes grades appear objective and fixed, when they are often malleable. It implies that students are powerless to affect the “official” grade.

9.3 Separating Feedback from Grades

9.3 Separating Feedback from Grades

Imagine you are sitting at a piano, practicing a piece of music. In order to get better—to play with greater success and accuracy—you need to be able to hear your own mistakes so you can practice those parts specifically. It also is helpful to have a piano teacher, an expert, who can guide you with more subtle feedback about intonation or phrasing. An expert can also point out places where you can improve that you didn’t even know were problem areas.

What you definitely do not need to know is that you got 87% of the notes right, or that your score for the piece was 26 out of 39, or that you played a C+. Such feedback, while it might give you a primitive, quick sense of how successful you were, is not all that helpful in the learning process. In fact, finding out that your playing is only a C+ might actually discourage you from practicing and improving.

What you need is ungraded feedback.

Giving feedback vs. giving grades.

The optimal role you can have in facilitating student learning is that of guide and knowledgeable mentor. When grades are the dominant form of feedback, that role gets conflated with the institutional power you have over the student. We need to find ways to provide feedback without the emotional baggage and power struggles that come with grades.

All of us, teachers and students alike, are members of institutions that require chronic reporting of progress in the form of grades. This obligation is becoming more dominant over time with the current emphasis on high stakes testing and measuring student and teacher performance. Since we must do it, we might as well do it right. In part, that means separating the essential function of giving feedback from the required function of giving grades. Ungraded feedback is desired as frequently as possible, while the role and frequency of grades should be minimized.

Feedback feels different from grades.

For a student, a grade lends itself to a sense of judgmental reaction, rather than direct and useful feedback. A big red letter at the top of a paper handed back to a student colors their reading of a teacher’s commentary (assuming there is one) that might otherwise be more useful to them.

Feedback is a striving for clarity about what is. Grades, especially poor grades, often instill a sense of what should be. For a student to identify her strengths and weaknesses realistically, she needs to have a nonjudgmental attitude about making mistakes. Poor grades often stir feelings of shame or anger, which are counterproductive to learning.

Feedback should always be formative.

The principle purpose of feedback is to help the student to become more discriminating and self-aware, and to identify any difficulties she is having. This understanding is only useful when it leads to an action that addresses the problem that has been revealed. Teacher feedback should help a student discern where she needs to take action and how to address the problems revealed by the feedback.

Feedback should accommodate students’ needs, both academic and personal.

For students who are shy or lacking in self-confidence, feedback that is visible to other students can be embarrassing. As the culture of the classroom evolves and students come to recognize the importance learning from mistakes, the judgmental posture many of them have will be replaced with a more useful attitude towards exposing mistakes without shame. This is particularly true for feedback on “high stakes” activities, like tests. There needs to be a sufficient level of trust between students before they will be comfortable sharing failure openly. This is discussed in more detail in the chapter “Study Groups”.

The effectiveness of grades depend in part on the frequency of their use.

A balance must be found between giving enough grades for a meaningful overview of student progress and giving so many that they reinforce the bad habits of academic materialism. When there is enough ungraded feedback, students will not be blindsided by, say, low test grades. Providing frequent updates on things like homework completion can help reinforce better habits until students can become more responsible and independent. It’s important to remember that these updates can be ungraded, or, as described below, self-evaluated.

Many schools insist on a required frequency of grade reporting, both to students and to parents. Working within those constraints can be challenging; it requires tenaciously holding true to the priorities you have for your students.

Feedback should be provided in as many forms and venues as practicable.

Feedback can come in a wide variety of shapes. It can be written or oral, formal or informal, quick or thorough. It can be used by a whole class, a small group, or an individual. It can be private or public. It can flow from student to teacher, from teacher to student, or between students. It can be structural, such as feedback that is built into the design of homework. It can come from peers, parents, or friends.

Matching the form of feedback to the needs of the moment requires practice, but as your repertoire grows, so does your responsiveness to the needs of your students. To that end, here are some of the many forms feedback can take, arranged from simplest and quickest to most sophisticated.

9.4 The Many Forms of Feedback

9.4 The Many Forms of Feedback

Snapshots

There are a number of ways to get very quick, very informal responses on the fly from students. These include:

Fist to Five. This is a means of surveying a whole class and getting a quick sense of their understanding by asking every student to hold up one hand and raise from zero to five fingers as a form of assessment. For instance, when you are about to have students review their homework, it is often worth asking, “How well did you understand the homework you just completed?” A five would mean “I finished it and understand it well enough to be able to teach it”, a four might mean “I finished it, but have some questions”, a two might mean “I didn’t finish it”, and, of course, a fist means “I didn’t do it”. Similarly, while lecturing, you might ask for a survey about how well each student understood what you just said. And if you want to know whether the pace of the class is appropriate, ask them to rate it where five means “I’ve got it, let’s move on”, and one means “You are going much too fast.”

Stoplight. You can give little slips of green, yellow, and red paper to each student. During a lecture, you can ask periodically for them to hold up one color. Green means “I understand, keep going”, yellow means “slow down, I need to hear that again”, and red means “stop! I’m lost”.

Thumbs up. This is a variation on stoplight, where a student holds a thumb up for green, sideways for yellow, and down for red.

Digital snapshots. If you have access to the necessary technology, there are, of course, a number of digital ways to do quick, informal snapshots. These can be feedback to the teacher, but can also allow whole class polling to be made visible by projecting results onto a screen.

Check-ups

These are slightly more formal and detailed feedback structures than snapshots. They typically involve asking a student to answer a question or two to show her level of mastery. Techniques include:

In-class check-up. This is similar to the ticket to leave, but can be given in the midst of a lecture, for instance, or following the introduction of a new skill. This might consist of a problem to be solved on a quarter or half sheet of paper. Once it is collected, the answer can be handed out or projected onto a screen; this can lead to a differentiated activity or “sharing the wealth” through conversations between those who got it right and those who didn’t.

Ticket to leave. Have a student fill out a quarter piece of paper answering a question, or writing a short statement about what she has learned in class. She turns that in to you as she is leaving the class. You can have her answer a specific question or write about what she thinks is the most important idea she heard today. The ticket can also be a reflective exercise, asking her to write about her experience in class, for instance, or how she is feeling about the pace of the class.

White boards. If you are working with material that can be represented visually — problem solving, graphing, questions with single word or short phrased answers, map-related material, etc. — one way to check up on student mastery is to have each student write an answer to a question with a dry erase marker on an 8 by 10 or larger piece of whiteboard. Every student then holds her answer up at the same time. Each student will need a whiteboard, a marker, and a 4 by 4 inch piece of felt or some other form of eraser.

Structural feedback

Feedback can also be woven into the workings of the class without requiring any active participation by the teacher or other students. For instance, homework can include mechanisms like helpful hints and answer keys that help students assess their own level of learning. These techniques are discussed further in “The Role of Student Work”.

Reflective writing. Whenever appropriate, students can be asked to write about their comfort with the current material, the pace of the class, or the classroom structures themselves. Reflective writing is explored in more detail below.

Steering committees. As described in “Creating the Classroom Culture”, creating a sense of student ownership requires structures that give them a voice. One way is to create steering committees of students who volunteer to discuss and solve issues that you or they feel need to be addressed. This is primarily a form of feedback from the student body to the teacher, and it can be a very powerful tool, indeed.

Learning Contracts. Whether you are using minicontracts or unit contracts, it is useful to leave plenty of blank space in the margins for your comments.

Formative assessments. As described in “Making Tests Meaningful”, if assessments are truly formative — that is, if there is a way for students to directly learn from their mistakes — then the quiz or test itself can be seen as feedback. The question of how to help students to see incorrect answers in this way is explored in the chapter “Learning Contracts”.

Mid-quarter reports. Many schools require teachers to fill out forms to communicate with parents about their student’s academic progress. No matter how this feedback appears — whether it’s a selection from a list of attributes or a short written or digital communication — it is often possible for students to participate in the process. If you are required to choose at least 3 attributes from a list, for instance, you can have students choose 2 while you choose a 3rd. If you disagree with the students’ self-assessment, that can lead to an important conversation about their level of self-awareness.

Grade conferences. The purpose of grade conferences is to have a conversation between you and each student in which you can also give them feedback on their performance and how to improve it. They can also give you feedback on how you can better help them. Grade conferences are explored fully below.

9.5 Other Considerations About Feedback

9.5 Other Considerations About Feedback

KISS.

In general, written feedback is most effective when it is timely and brief. Long written responses by a teacher may be useful for some students, but will be skimmed or ignored by many. In general, the more you write, the less likely it is that they will read it. Given the amount of effort and time required by teachers to respond to student work in writing, this method is inefficient on both ends. When complex ideas need to be communicated, conversations are much more effective than written comments for most students. Fortunately, open work time creates opportunities for such conversations.

Feedback trains your students in metacognition.

When your students are given feedback regularly, it helps them develop a clear sense of whether and how well they have mastered the material. It should be done with the intent of training them to internalize a sense of excellence.

Feedback takes courage.

The giving and receiving of feedback can make students feel vulnerable. When a student discovers she did badly on a test, her initial reaction may be one of shame, sadness, or anger, all of which preclude learning from her mistakes. She is unlikely to get good feedback from you or her fellow students when all she wants to do is bury the incriminating test in the bottom of her locker as soon as possible.

This kind of response comes, in part, from a judgmental posture towards making mistakes, and especially from failing at anything. Unfortunately, this attitude can be deeply ingrained, since it is regularly reinforced by the habits of doing school; if success means getting good grades, then failing a test is a disaster to be avoided at all costs. The fear of failure can drive students to cram more diligently before a test, but also trains them to be risk-averse and sets up a counterproductive attitude about learning from mistakes.

Students must therefore be trained to understand that making mistakes and learning from them are essential components of the learning process. Mistakes can be seen as clear and useful information about what a student hasn’t learned yet and still needs to work on to be successful. This shift in perception can only occur when the classroom culture is grounded in a better understanding in how learning actually works, and in replacing the old habits of doing school with the common goal of self-directed learning.

Feedback can also be frightening for a teacher as well. Asking for honest responses from your students about the changes you are making in your practice can make you feel vulnerable. You may be afraid that students will take advantage of your openness to criticize or attack you. However, even such abuses can provide teachable moments about the nature of effective feedback and how a community works. By honestly and dispassionately responding to a student’s inappropriate remarks (no small task!)56655, the whole class can learn to distinguish between useful and hurtful criticism. Drawing an analogy to an art critique can also be helpful. The aim of such feedback is to help the artist see her work through the eyes of others, with the common purpose of improving everyone’s skill as artists.

It is important to confront such fears directly. If you want to change your practice, there is no more important factor than listening to how those changes are perceived by your students. Just like an architect who tries to design a hospital without ever talking to doctors, nurses, or patients — it is simply bound to be less effective to design a class without student input.

On the other hand, you need to be comfortable with the pace of change and the level of exposure you feel in how you handle that change. Taking on too much perceived risk is as counterproductive as being overly cautious. Finding the balance is key.

What is needed to allay these all these fears of students and teachers alike is a bedrock sense of trust within the community. That is why it is so important to create a classroom culture that requires true mutual respect from every member.

9.6 The Benefits of Self-evaluation

9.6 The Benefits of Self-evaluation

Another strategy for redefining the purpose of grades is to hand over the function of grading to the students themselves, as often as is practical.

Self-evaluation has a powerful effect on student well-being and performance.

Simply having a voice in such an important matter as grades boosts student self-confidence and stature. It increases the sense of ownership the student has in her own learning process. Furthermore, the experience of being trusted to determine her own grade trains her in how to be trustworthy; it encourages a sense of purpose and responsibility, which makes the learning process more meaningful.

Self-evaluation teaches students to internalize the nature of excellence.

Rather than expecting a teacher to tell her “good job” or “this needs improvement”, a student who regularly self-assesses begins to know what a good job looks like without any external prompts. The internalized ownership of what excellence looks like is an essential aspect of being a responsible and self-directed student.

Self-evaluation boosts student metacognition.

By assessing her own work, a student starts to become more self-aware, more conscious of what she has and has not yet mastered.

This is true for both curricular goals and the cultivation of desired character traits. Having a student reflect on and evaluate intangibles like self-directedness and how well she collaborates and engages in the classroom boosts her self-awareness of those traits. These self-evaluations, in turn, can lead to powerful conversations, particularly during grade conferences.

There are some aspects of a student’s performance that she knows better than you do. Allowing a student to express how well she thinks she did in areas such as participation in a study group, self-directedness, or engagement in discussions gives her the power to describe how well she is doing at the job of being a student. It also gives you insights into her experience and provides valuable information in helping her to improve her performance.

Student self-evaluation frees up teacher time for other, more productive activities.

If students can effectively assess their own work, much of the time teachers spend grading can be used to better purpose. Giving feedback can become much more focussed and dramatically less time-consuming when it is divorced from evaluating every aspect of the students’ work.

Self-evaluation improves the relationship between student and teacher.

Giving students the responsibility of evaluating themselves rearranges the unspoken power structure in a healthy way. You are no longer doling out points, a process that is fraught with real and perceived injustices and abuses of power. This can reduce the students’ pervasive sense of powerlessness, which, in turn, reduces the power struggles that often result. Instead, students see themselves as more self-reliant and responsible, and grades evolve into more natural consequences of the work they are doing. A result of this shift is that there are dramatically fewer legalistic arguments about grades.

The idea that students are capable of evaluating their own work and having a say in their own grades is a difficult one for many teachers to accept. They believe that students will game the system and be dishonest in their assessments. And, to be fair, unless the classroom culture changes so that self-directed learning replaces doing school, students will continue to game the system. The goal is to change the classroom culture and foster the ability to self-evaluate honestly and effectively as an integral part of the learning process.

9.7 Modes of Self-Evaluation

9.7 Modes of Self-Evaluation

Students can be given a voice in assessing a wide array of the work they are doing. They can also be reflective about how well they are performing the role of learner. Here are some of the basic modes that self-evaluation can take.

Evaluating understanding / mastery.

Metacognition occurs when a student is genuinely learning new material. When she is reading, for instance, it is critically important for her to be aware of how well she understands what she is reading. This will steer what she does next. If she doesn’t understand a word or a phrase, for instance, making note of it can lead her to dig deeper and do some research, or write down a question to ask her teacher or her study group when she gets a chance. Simply assessing her level of understanding can cause her to recognize the need to get help from others.

Assessing her understanding can be done in very simple language. One scheme is to use a 1 - 5 scale, where 5 means “I can teach this”, and 3 means “I still have some questions”. A form using this system is shown below.

Another, even simpler approach is the stoplight analogy:

“G” stands for green, meaning she is good to go and can continue on to the next topic,

“Y” stands for yellow, meaning she needs to slow down and pay better attention to the details,

“R” stands for red, meaning “stop, I need help”.

As always with feedback, this kind of self-evaluation should not be graded so that the student’s appraisal of her work will be honest. Self-assessing understanding is discussed more fully in “The Role of Student Work”.

Evaluating the learning process.

In this form of self-evaluation, the student is not being asked how well she understands the material, but rather how well she did the work of trying to learn it. It asks whether she is solving problems completely, completing an assignment by a given deadline, making corrections as needed, and whether she did everything she was able to do by herself. Because this evaluation is based on more external criteria than that of understanding and mastery, it is more appropriate for it to be a part of a student’s grade.

Such an assessment can be made for each piece of student work. It can also be made for a learning contract, as described below.

Here is an example of a rubric that combines the assessment of mastery and process. Note the student-friendly language used in both scales. (Thanks to David Allen of Evanston Township High School for the next three forms.)

Student reflections.

The modes discussed above are useful for self-evaluation of many curricular-based aspects of student work. However, there are other, less quantifiable aspects that need to be assessed as well, such as character traits. Tenacity, collaboration, and self-directedness are all vital to learning. One way to assess these traits is to have students answer a set of questions about their performance in class, as described in the section on “Implementing Grade Conferences” below.

But often, the most appropriate approach is to have students write about their own perceptions of how well they are doing as learners. The central task in guiding students in this kind of work is to balance offering enough direction to guide them in self-reflection, with keeping things open-ended enough to encourage creativity in their writing.

It is also important to find the right frequency of asking for self-reflections. In particular, if required too often, feedback becomes a pro forma exercise and not as meaningful for the student or you. Varying the scope and format of the feedback can also help keep the process fresh.

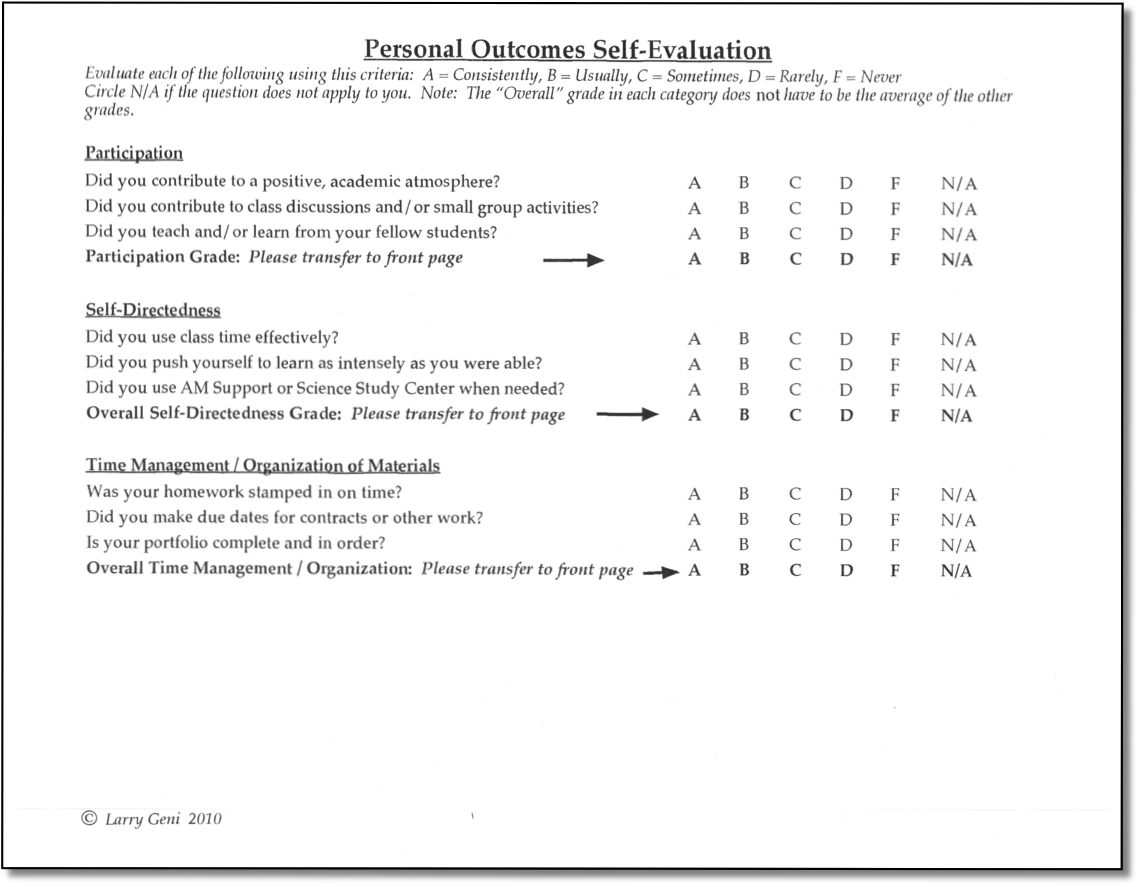

Here is another example of guidelines for reflection, this time at the end of an AP Psych unit, after students have completed the unit test. In this case, the students are asked to evaluate how well they mastered the material, how well they prepared for the unit test, and how well they performed several “personal outcomes”, like time management and self-directedness. In addition to assessing these items quantitatively, they are also asked to write about them.

The second page asks them to further discuss what they will do next, based on the results of this unit. How will they learn from their mistakes? How will they improve how they prepare for the next unit test?

9.8 Self-evaluating Learning Contracts

9.8 Self-evaluating Learning Contracts

When students work on learning contracts, they can evaluate each individual item they worked on as well as the entire contract. Furthermore, for each contract item, they can evaluate 1) their mastery of the content and/or 2) how well they worked through the process (i.e., making deadlines, completeness, correct format, etc.).

When evaluating a short minicontract, (say, for one or two class periods of open work time), an evaluation of the entire contract may not be necessary or appropriate. On the other hand, when evaluating a three week unit contract, an evaluation of the entire contract provides an important overview of how successfully each student is doing the process of learning.

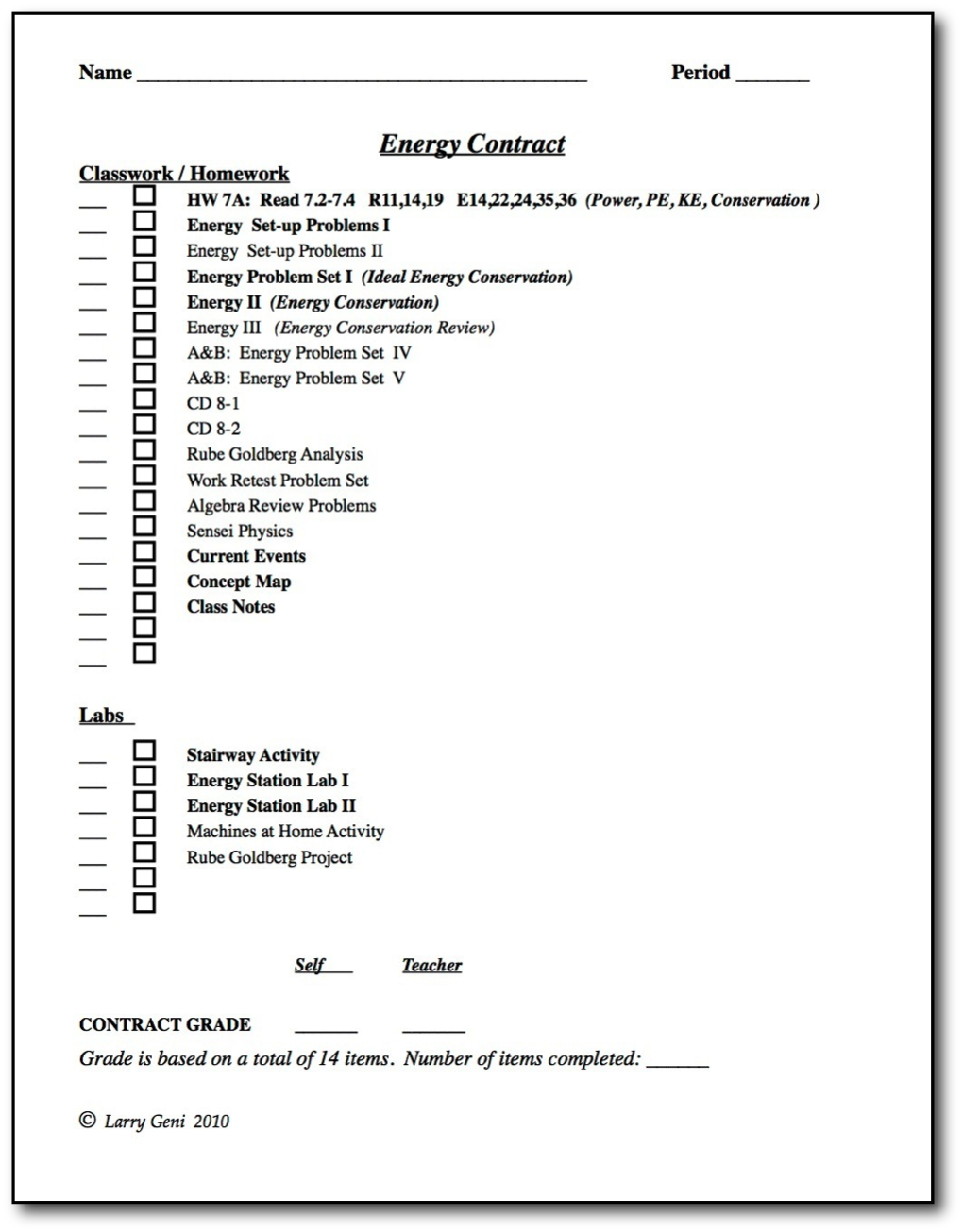

On the next page is a form I created to define guidelines for self-assessment of all the work found in a unit, as well as the rules for self-evaluating the entire contract itself. for clarity, an example of a typical unit contract follows the form.

After evaluating each item that they accomplished, they would give themselves an overall contract grade, located at the bottom of the unit contract. This grade would be based on their evaluation of each item and how many items they completed, with a penalty for not completing the minimum number — in this case, 14 items. Not completing required items caused a further grade penalty.

While it is possible to fully quantize this kind of overall contract evaluation, my emphasis on removing points from the classroom caused me to intentionally make the process “fuzzier”. While there were well-defined guidelines — “missing a required item on the contract lowers the contract grade by one letter” — I asked students to use common sense in balancing all the factors going into the grade. I did not create a specific weighting structure for the individual items on the contract, even though some items were much more important or challenging than others, but rather asked them to do that balancing on their own. Since I also gave each contract a grade, (located right next to theirs on the bottom of the page), any significant differences in their evaluation and mine became immediately obvious and led to a conversation about that discrepancy. Sometimes, those conversations proved important in challenging a student’s continued habits of doing school.

Here is another example of a contract evaluation scheme. In this case, it is mastery that is being evaluated. (Thanks to Vanessa Brechtling of Niles West High School).

9.9 Implementing Student Self-Evaluation

9.9 Implementing Student Self-Evaluation

Whenever practicable, have students evaluate themselves.

Take a good look at everything that you now have grades for, and ask whether it is truly essential that you do the grading for all of them. The balance between student and teacher evaluations will depend, as always, on the maturity and readiness of your students, but also on your own personality. Allowing students to self-evaluate gives them some of the power you once had. Seen from this point of view, it reduces your leverage in affecting their behavior. Nevertheless, when looked at candidly, there is often no compelling reason to block students from evaluating their own work. The loss in leverage is generally more than offset by gains in student motivation and ownership of the learning process.

The frequency with which students need to turn in their work for your direct evaluation is determined by how often they need your written feedback, as opposed to discussing their work in person or having their study group giving them feedback. Depending on the nature of the work, written feedback might need to occur daily, or as rarely as once per contract. It will probably be more frequent at the beginning of the year when you are still establishing the standards of excellence, and less important later, when students have learned to be better at self-evaluation and study groups, and other support structures have become more effective in supplementing your feedback.

Make timeliness part of the evaluation, if it is appropriate.

Some student work has a hard deadline, and the work will be more valuable in the learning process when it is done on time. For instance, if students must complete their homework in time to participate in a study group conversation, the deadline is not flexible. Doing the work and being ready for the discussion makes it a much more valuable learning experience than showing up cold. Therefore, any self-evaluation of late work should reflect that the work is now less valuable.

One way to distinguish work that has been done on time from that which hasn’t is to use a stamp. (If the work is done digitally, it may be more of a challenge to find a suitable marker for timeliness.) Here are a few ideas about how to think about and implement their use:

Receiving a stamp can legitimately be part of the value of the homework. My students, for instance, evaluated how well they did the homework process on a 1 to 5 scale, as seen below, where a “5” meant excellent work and a “1” meant a minimal effort. Work that was completed after the deadline (and therefore did not receive a stamp) would be rated a maximum of “3”, meaning it was a mediocre effort. A stamp should be a prerequisite for excellent work.

The stamp serves a number of functions. It marks the transition between the individual effort and the conversational learning that follows. The stamp is an easy, clear record of how often students make deadlines or complete homework, which can be useful in helping students with procrastination issues or other impediments to completing work. It is also surprisingly effective in motivating students to do homework. It can boost the peer pressure — if everyone but one person gets a stamp, there is a sense of the one who didn’t do it having let the group down. This can be amplified by giving everyone in the group a “double stamp” if they all receive a stamp. This doesn’t have to be “extra credit” — in my experience, it works remarkably well as a strictly symbolic gesture.

While it may be useful to stamp their work with a date stamp, there are several disadvantages; they are readily available and can therefore be easily faked, and they are unimaginative and utilitarian. Using a playful stamp is a way of injecting fun into the process. It is worthwhile to accumulate a collection of stamps over time and vary them as you see fit.

The role stamping work can have in boosting responsible behavior, not to mention increasing homework completion, is described in detail in “The Role of Student Work”.

Teach students to be honest, skilled self-evaluators.

Training a student to evaluate herself accurately and honestly is essential, particularly at the start of the year. A student may or may not have the metacognitive ability required to assess her own work, but this is an important skill for her to develop, and one that makes her learning process much more effective.

It is important to begin by teaching students to evaluate one aspect of their work at a time. I would have my students evaluate reading homework first and give them intensive feedback until they were largely self-sufficient. Then I would have them self-evaluate their lab write-ups, followed by self-assessing their work on problem sets. Since each type of work has its own criteria for excellence, each form of self-evaluation should reflect that. Within each format, only those aspects that contribute to the work being excellent should be evaluated. If timeliness doesn’t matter, for instance, don’t have it be part of the evaluation. That means clearly articulating the difference between hard and soft deadlines.

The process of teaching students how to self-assess can be accelerated by using self-evaluation forms like the one below at the start of the year. This way, there can be direct, immediate feedback on how honestly and accurately students are self-assessing. These forms need to 1) define clearly and concisely what aspects of the work make it excellent and 2) have a simple scale of evaluation. Designing such a form well means that there will be less overhead for you in managing your feedback to your students, and you will be able to respond more promptly..

Here is a sample form my students used to self-evaluate their homework. The upper section describes the criteria of excellence for this type of work. The lower section defines a common-sense scale of assessment. When you are reviewing how a student used it, any aspects of their work that are missing or incomplete can be simply highlighted or circled on the form. This is more direct — and more likely to be read and understood by the student — than writing out long descriptions of the problem. By helping a student isolate the specific difficulty he is having with the self-evaluation process, you are cultivating her metacognitive skills. You are also providing a succinct explanation of why your evaluation was different than hers.

Placing the student’s and teacher’s grades side by side shows the level of agreement clearly. Disagreements between you and your student about the appropriate grade can lead to meaningful discussions with her about what she believes excellent work and excellent learning actually look like. These conversations can bring her basic beliefs about her own capabilities to light. Since these beliefs are often instrumental in blocking effective learning on her part (“I’m no good at math”), this can be a powerful moment of growth in self-awareness and self-reliance.

Using other students’ work as exemplars can also clarify what excellent work looks like and can allow a student to zero in on what aspects of her work need improving. However, showing other students’ work must be done carefully and non-judgmentally. The issue is not about comparing one student’s work to another’s; exemplars are merely tools to help clarify how to improve. It helps to show student work that is anonymous.

Trust, but verify.

Students need to know, especially when you are establishing the roles you and they will play in the classroom culture, that you are truly giving them power to assess themselves and that you trust them to be able to do this honestly. Many students will be skeptical and assume that it is an example of fake responsibility or a trap you have set for them. It may take time for them to accept the new classroom culture as genuine. It is essential that students understand that you intend to help them overcome their misguided and counterproductive desire to accumulate points. Together, you will replace that desire with the ability to appraise and steer their own learning more effectively and honestly.

Mutual trust is the cornerstone of the classroom structure. It must also be clear to students from the beginning that they can abuse that trust, but that if they do, they are losing something important. It is the fear of losing your trust in them, not the fear of being punished, that will ultimately allow them to see that cheating is self-destructive behavior.

Part of establishing this culture and your working relationship with your students is to convince them that self-reliance and honest self-assessment are important life skills that you will help them learn, if they don’t have these skills already. Many students will quickly (and often enthusiastically) take ownership of the process of self-assessment. For those who struggle with it, the struggle can lead directly to conversations which may be more important and meaningful in their lives than any of the content that they may learn in your course.

A typical opportunity to direct a student towards honest self-assessment occurs when her results on tests are much poorer than her reported evaluation of her homework covering the same material. Diagnosing why this discrepancy happened together with the student helps clarify the usefulness of honest self-assessment. If she knowingly boosted her homework assessment order to get a better grade and avoid doing needed additional practice, the direct result that she was unprepared for the test. That’s clearly not in her self-interest. If she did badly on the test due to test anxieties, despite having mastered the homework, that is a specific challenge that needs to be addressed separately. If she was surprised by her poor test grade (“I thought I knew it”) that is a different problem: She was simply not conscious of the aspects of the homework that she hadn’t yet mastered. That means that she needs training in paying attention to the signals that indicate she still requires more practice. In other words, honest self-assessment is in her best interest.

Keep it simple.

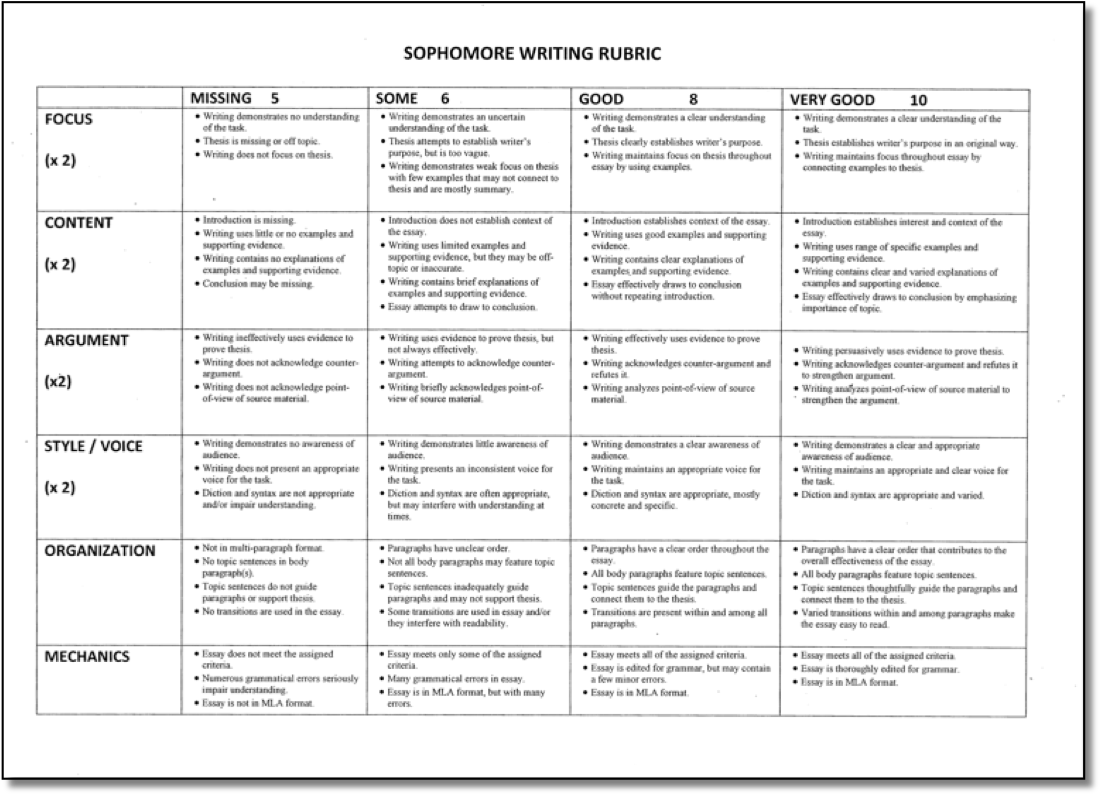

Students need a structure to direct their self-evaluations: a way of defining what excellent work looks like and what is missing when it isn’t excellent. This often takes the form of a rubric. Unfortunately, such guidelines are often complex grids, using language that is alien to many students. Here is an example of a student unfriendly self-evaluation form.

If the purpose of self-evaluation is to cultivate metacognition, then the structures we give students must not be forbidding and off-putting. One of the central tenets of effective communication is to speak to students in their own language. Even though it may be useful for you to have learning goals defined in great detail using language that you understand as a teacher, such language will be a barrier for students, particularly those who are immature or academically unsuccessful. What students see should be as simple and direct as possible. If it can be expressed in 10 words, don’t use 13.

The complex grid shown in the matrix format can be completely replaced by the form below. Every aspect of the criterion for success, listed in the right hand column of the matrix, has been translated into language that is more accessible to students. Yet it still gives the teacher the ability to give specific feedback on aspects that need work. Notice that even the evaluation scale has been dramatically simplified and translated into language that any student can understand and use. (Thanks to Steve Wool of Evanston Township High School.)

9.10 The Benefits of Grade Conferences

9.10 The Benefits of Grade Conferences

"My grade was never handed down from above, but was one that I believed in and so did you. I had just as much a say in it as you did, which made it equal and fair. It also brought you a little farther down off the pedestal of teacherdom, too. Too many teachers are so far removed, so almost celestial, bestowing grades upon us and never saying why or how. This was real, and very personal." — Katherine J., student

In many traditional classrooms, the question of what factors contribute to a grade means balancing test scores with other factors such as homework completion. However, if we are in fact preparing our students to live their lives well, we must also value other, less quantifiable, aspects of a student’s performance. Perhaps she has become a more self-directed, metacognitive learner. Perhaps she has assumed a more adult posture of responsibility and is managing her time more effectively. If such things matter, they should be a part of the grading system. Given the personal and subjective nature of such factors, it is appropriate to engage students as an integral part of the process of evaluating them.

The end of a marking period is an opportune moment to stop and reflect with our students what they have experienced (and not just academically). It is an appropriate time to discuss how they can learn from their experiences and become better, more self-sufficient learners. It is time, in other words, for a meaningful conversation.

Grade conferences serve a number of important functions:

Conferences provide you with a deeper, more meaningful understanding of a student’s experience than any other source of information you may receive.

Conferences boost a student’s self-awareness of her strengths and weaknesses.

Conferences offer an opportunity to model the skills of setting goals and learning from mistakes.

Conferences hold students accountable, particularly when conference grade summaries are reviewed from one marking period to the next. By looking at comments from a previous conference, students can see whether they have followed through with agreed-upon changes in how they work and learn.

Conferences boost the student’s sense of ownership. The very fact that there is a discussion to be had, rather than you “giving” them a grade, redefines the traditional power structure in a healthy way. This is a part of the student’s academic life where having a voice is particularly important.

Conferences teach students organizational skills and responsibility for maintaining the collection of their work.

Conferences allow for the appropriate level of flexibility in determining grades. There are important but non-quantifiable aspects of the academic experience, and a grade conference can incorporate those aspects into a final grade.

Conferences generate trust between you and your students, because conferences require trust from both parties. This, in turn, deepens the working relationship between you.

I found grade conferences overwhelmingly to be a satisfying experience. I rarely disagreed with my students’ self-evaluations and even more rarely found myself engaged in a power struggle about finding an appropriate grade. The conversations were often the most personal and meaningful to the students that I would have with them and regularly transformed and improved my working relationship with them. Grade conferences established the idea that both the student and I were working for her success and growth.

9.11 Implementing Grade Conferences

9.11 Implementing Grade Conferences

Portfolios: the basis of the conversation.

In order to discuss the work the student has done, that work should be readily available. Looking through it together will allow you and your student to get an overview of and observe trends in her work, to notice whether she has responded to comments or learned from mistakes. Seeing the range and quantity of work that has been accomplished is also an opportunity to celebrate the effort she has put into the class.

What does the physical portfolio look like? Where is it stored? What student work is actually collected, and how is it collected? How often will the portfolio be made available? The mechanics of the portfolio will depend on the subject being taught, the level of responsibility of the students, and the space constraints in the classroom. I found that providing every student with a hanging file folder worked well. The folders went into freestanding stacking bins, one per class, and they were stored on the side of the room. Students learned quickly to store their tests and their contracts in their portfolios.

Of course, student work is increasingly completed in a digital format. Clearly, you must create a system of organizing that work in a way that is analogous to a physical portfolio. The use of physical and digital uses of portfolios is described further in “The Role of Student Work”.

The grade conference form

The structure and content of a conference should take a form that summarizes what you and your student are bringing to the conversation. If well-designed, the form will serve a number of functions:

Defining all the factors contributing to the grade. Your school may constrain how a grade is derived. Obviously, the form you design will have to take these constraints into consideration. Still, it is worth remembering that grades are fundamentally subjective, and the form is, at its root, a form of communication between you and your student.

Providing the relative weight of each factor in the grade, and therefore defining its importance in determining the grade.

Reporting all the grades collected in your gradebook.

Giving the student a voice in self-evaluating her performance. The form defines what attributes are valued and gives a mechanism for self-evaluating them.

Making a student’s strengths and weaknesses visible.

Allowing a comparison of your perception of the student’s performance and her own perception. Differences often lead to meaningful conversations.

Allowing for some flexibility in determining the final grade, which can be well-defined or left open to discussion.

Allowing for commentary, responses to the strengths and weaknesses displayed by the student, and plans for improvement.

Documenting the status of the student’s learning experience at that moment and allowing for comparisons and the analysis of trends over the course of the year.

As always, good graphic design improves the functionality of a grade conference form. There should be plenty of white spaces available in the margins, as well as a place for both student and teacher evaluations and comments. All the relevant information, like the percentage weights of different grade factors, should be clearly discernible.

A sample grade conference form is shown below.

Finding the time

Conferences take time. This is a central impediment to be dealt with. In my experience, conferences averaged about five minutes per student. Multiplying that by the number of students, and allowing for occasional breaks to instruct the class and check on how they were doing, and I generally found it necessary to dedicate three or four class periods to the process. If you consider repeating this at the end of every marking period, (in my case, four quarter grades), it might seem like a daunting amount of time.

It is important to remember that our intention is to foster self-sufficiency and responsible behavior in our students. By the time the first marking period is over, they have had many experiences of open work time, where their activities are not being directed by you. This will make them better able to be self-sufficient and self-directed while you are busy with individual conferences. More importantly, the culture has hopefully evolved so that they recognize both the importance of these conferences and their own capability of working independently.

Boost efficiency by reducing the transition time. The amount of time needed for conferences can be made shorter by optimizing the efficiency of the process. This entails carefully defining what a student must prepare for the conference, as well as conveying the importance of making the transitions between each conference as smooth as possible. The mechanics of this process are described in detail later in this section.

Hold some conferences outside of class time. Depending on your schedule and those of your students, it may be possible to hold a number of the conferences outside of class. With incentives (such as having an early conference), some students may volunteer to meet before or after school or during a free period.

Classroom activities during conferences

The question remains: while you and one student are in a conversation, what is the rest of the class doing? It is, of course, essential that this time remains productive for them.

Here are some activities students can do during conferences:

Extended open work time. Define a contract with more optional work available and a higher minimum number of contract items. This requires careful planning on your part, both in defining the optional work and timing it to match the conference schedule.

Projects. I have had students work on a goal where several days are required to, say, build some object for a competition that embodies principles we have studied. For instance, I might have them create a “Rube Goldberg” contraption that uses simple machines and the principle of energy conservation, which must be explained before the machine is actually used.

Useful audio/visuals. I rarely showed movies in my classes, but if there were any that were truly useful and relevant, I would save them for the conferences.

Independent research. If your school has a computer lab, scheduling the conferences there allows students to pursue a range of topics and report what they have learned immediately following the conferences. Of course, a library or research center would also serve.

Extended study group work. Timing a contract so that students can do homework that will be discussed in study groups, followed by self-administered check-ups, can occupy one or more class periods.

Any combination of these strategies can be used, and you may have many other options available, depending on the discipline you are teaching and your school’s facilities. For some teachers, it may be possible to do a number of conferences outside of class. For instance, my physics classes met seven periods every week, with three periods free as study hall time for my students. During those periods, students often volunteered for conferences. I also had a homeroom duty that provided some time for meeting with students.

When to have conferences

The most obvious time for grade conferences is just before the end of marking periods, when permanent grades must be generated. If it is not possible to complete the conferences before the end of the marking period because, say, it’s the end of the semester and you can’t generate a semester grade until after the exam has been scored, then you might choose to have a conference summarizing those things which have already been completed.

In some cases, it may be possible to extend the timing of grade conferences beyond the due date for grades. For example, if a student agrees with you about what her marking period grade is, a conference can occur well after grades are due. This allows you and the student to still have the same meaningful conversation that you would have had before the due date.

Where to have conferences

In general, the conversation you have with each student must be private enough for an honest exchange without fear of being overheard. The size of the room and the number of students are, of course, major factors in how much privacy is possible. Depending on how well you can trust the class to operate independently while you are holding conferences, you may need to be within sight of whatever activity the class is doing, or you may be able to hold conferences outside your classroom. You may need to vary the location of the conferences based on changing circumstances, class behavior, and what activities they are working on.

The sequence of conferences

There are several factors in deciding the order in which conferences are run. Doing them in a sequence, such as alphabetically, gives students lots of warning about who is up next, which can improve efficiency. On the other hand, running them in a random order requires everyone to be prepared from the start, which can create a sense of readiness in the class.

Some conferences will be more problematic and take more time than others — there may be serious disagreements between you and a student that need to be resolved. You may choose to do the difficult conferences first so that you have time to do them justice or come back to them if there isn’t a timely resolution. If possible, it may be preferable to have those conferences outside of class, both for the sake of efficiency and privacy.

Tips on running conferences

Be prepared. Have all your materials ready before the first conference begins. These may include your gradebook, whether physical or digital, the grading scales used for tests or other assessments, a calculator, and office supplies like a stapler, paper clips, and highlighter. Similarly, each student should be prepared to show up with all her materials, including her portfolio, with all non-digital materials organized and ready to lay out on the conference table, her journal, and any other evidence of learning she may have.

You need to be very explicit about what students must bring with them and how it should be organized. This is particularly true during the first conference. If a student is unprepared, you can bump her to the end of the line and have the person who is “on deck” take her place. There should always be two students getting ready to meet you while you are working with the current student.

First things first. Remember that the cultivation of a responsible, honest posture in the student is the goal. Grade conferences can make a student’s lingering habits of doing school visible. If she has a dishonest or manipulative attitude and is trying to get away with something, that should become the topic of discussion. Bring the conversation back to the question of whether she is genuinely learning, rather than engaging in a legalistic argument over what her grade should be. This reminds her what really matters and helps her see her academic materialism for what it is. Deciding on a grade will come later. Reacting negatively to a student’s efforts to get a grade that is better than what she has earned will only shut down the conversation and prevent the student from learning from the incident.

Be non-judgmental. Whatever the student has or hasn’t accomplished academically, it’s grist for the conversation. It is essential that any feelings a student has of shame or anger over poor grades are allayed and replaced with a positive response. That begins with your being a role model in looking at a student’s mistakes and failures with a nonjudgmental posture. It is all just feedback about what the student hasn’t learned yet.

A student’s behavior during the conference itself may also require a sense of equipoise on your part. Perhaps the student is angry about the grade, or depressed, or wants to manipulate you into giving her a better grade. All those actions can serve as the starting point of a conversation that leads to the student having better self-awareness.

Talk less, listen more. This can be quite difficult, especially with a student who is reticent to speak up for herself or disagree with you about her grade. Besides, most teachers I know (including myself) like to talk, to explain, to teach. Remember that one of the purposes of grade conferences is to give students a voice in evaluating their academic progress.

Ask the student for her perceptions about problem areas before telling her your observations. It is important to know whether she even sees and can articulate any problems she is having.

Come up with a plan together. Grade conferences should result in a specific plan for how to improve every student’s performance and experience. While it may be tempting to rush in with your own solutions, it is better to wait. If a student can come up with a plan for resolving current issues on her own, she will be much more likely to follow through than if it is your idea. Therefore, don’t offer suggestions to her unless she is unable to do so herself.

All ideas for improvement should be written as comments on the grade form. That way, there is a record that can be reviewed during the grade conference at the end of the following marking period. By the end of the year, these forms can create a clear record of the arc of the student’s experience and how well she has learned from her mistakes and improved her performance.

Discuss and celebrate the student’s successes. Positive reinforcement generally works better than criticism. While it is important to identify problem areas, it is equally important to recognize progress and success. Such celebrations can be pivotal for students who suffer from a fixed mindset. It shows that their self-imposed limitations can be overcome.

Adjusting, Compromising, Bargaining. Remember, all grades are subjective, no matter how precisely they are calculated. A final grade for a marking period should be the culmination of a conversation. This is not to say that you are negotiating with the student in order to come up with a settlement. Rather, you are working to find consensus on what a fair grade should be.

Certainly, the factual basis for the grade, as laid out in the grade conference form, is well established. Test grades, homework completed, etc., are not controversial. Other factors, however, can affect a final grade, including trends in a student’s performance and academic success, how she has responded to suggestions from the previous marking period, how challenging it has been for her to accomplish the specific goals she has been working on, and so forth.

It is also possible to legitimately bargain with the student, particularly when determining interim grades. The grade being discussed can be provisional, depending on the student’s ability to accomplish certain agreed-upon goals during the next marking period. These goals and the provisional nature of the current grade must be recorded on the current grade evaluation form, so they can be reassessed during the next grade conference.

Most importantly, student voice matters in any conversation. Your ability to read how genuine a student’s point of view, concerns, or requests are is paramount. This requires trusting your students and, at the same time, being attuned to their motives so as to discern when they are trying to game the system. When that happens, the fact that they are doing this needs to become part of the conversation. Why is gaming the system more important to them than the act of genuinely learning and earning a grade based on their accomplishments? Such conversations can be the most important of any grade conference.

9.12 Guidelines for Creating an Effective Grading System

9.12 Guidelines for Creating an Effective Grading System

"I feel that I learned more in this physics class than in any of my other classes because of the way classwork and grading was conducted. I was never worried about what my grade would be at the end of the quarter or semester, because I had faith in the way you graded and evaluated us. In all of my other classes I continually stressed out about my grade and always had to make sure that they were good enough." —Gabriella B., student

Keep your eyes on the prize.

We communicate our values with grades. In a grading system based on the curriculum transfer model of school, the only thing that matters is how much of the content the student has nominally mastered. Test scores and other assessments of learning will typically carry great weight in determining a grade.

If, however, we start from the bedrock belief that the purpose of school is to prepare students to live their lives well, we must shape our grading system accordingly. Every aspect of the grading system must been seen through this filter. Because we understand that tests rarely distinguish between genuine, long-lasting learning and “mastery” that will be forgotten in a few days or weeks, we must change the way tests are used. We must also look for other means of assessing learning that can supplement testing.

Furthermore, with our new framework — the Student Agency Model — the personal growth of students becomes much more vital. Training students to be internally motivated, responsible learners is more important than, say, whether they are punctual. When designing the “formula” for grades, all our priorities must be founded on self-directed learning. This must be the basis for the relative weights of what we are measuring.

Grades are of one of the most important structural factors that will affect whether your students are doing school or becoming self-directed learners. If we are preparing them for life, our grading structures must be designed to steer them away from meaningless activity and towards a relationship with learning that is intentional and rewarding.

An effective grading system fosters communication.

Your grading system should include regular communication between you and your students. Optimally, this feedback will come in a range of formats, not just points. Self-evaluated contracts, portfolios, quizzes and tests, test re-submittals, and grade conferences are all possible pieces of a final grade. Creating a form that summarizes all these aspects can serve as a basis for generating appropriate and authentic grades. An example of such a structure is described in detail in the section 9.13 below.

Grades should reflect a nonjudgmental posture.

If we want students to acquire the skill of learning from their mistakes, our grading system must avoid penalizing mistake-making as much as possible. This is even true for mistakes in judgment, like copying someone else’s homework. It is more important to teach students to act responsibly than to train them to not make mistakes out of fear of getting caught. In other words, be sure your grading scheme is not overly punitive in nature. Our goal is to cultivate integrity, not compliance.

If you want to be nonjudgmental in your working relationship with your students, your grading system must reflect that. Generosity of spirit can be built into an honest system of evaluation.

Intentional imprecision.

Recognizing the limits of precision in grading certainly runs counter to the current focus on data collection. But quantification is, in itself, often misguided and counterproductive. Using a 13-step scale from A through F, for instance, leads both student and teacher to focus on the difference between a B- and a C+, rather than on how much the student has learned. Besides, how precisely can learning be measured? Even more problematic, how precisely can traits such as grit or self-directedness or creativity be measured?

Whenever possible, use means of measuring learning with as few decimal places as possible. Having a student receive a 3 on a 1 - 5 scale, for instance, is less fraught than getting a 62.6% on homework mastery. Creating “soft” rubrics — replacing a complex and overly defined structure with less specific quantifiers of evaluation — helps avoid student preoccupation with collecting points. Whenever possible, try to avoid direct translations to letter grades.

A flexible interpretation of the importance of different aspects of the grading system also helps ground feedback in personal meaning for the student. For instance, rather than defining the three factors in a marking period grade as

Evidence of Work - 40.0%

Evidence of Learning - 40.0%

Personal Outcomes - 20.0%,

the same information can be communicated effectively without the unnecessary precision, as seen in the diagram to the right.

Use points only when necessary.

Distinguish between the aspects of grades that are overtly quantifiable, like the number of correct answers on a multiple choice test, from those which are not, like how much effort a student has put into the learning process, or how well organized her written journal is, or how well she collaborates with her peers. The lack of quantification itself leads to more meaningful conversations about these topics.

One legitimate function of points is to quantify the relative weight of different activities. Another is to keep track of how many questions a student got right out of the total number of questions asked. In your subject, with your students, you may find other situations where points are the only practical way to derive grades. Nevertheless, there are some serious disadvantages to point-based grades that are worth thinking about.