Starting the Year

Starting the Year

The best time to establish the right classroom culture is at the start of the year. When your students walk in the room, they want to know who you are and what their experience in your class will be like. This is the moment when they are most open to a new way of operating in the classroom. It is also the best time for you, as it follows a summer when you have hopefully had the most time to prepare new approaches and think through how to implement them.

Part I: The First Day

Introducing Yourself and Your Course

Part I: The First Day

Introducing Yourself and Your Course

"From the first day when I walked in the room I could tell it was not going to be the regular boring old class that I’m sadly accustomed to. There was a different lighting in the room, and a different feel in the air. I don’t think that feel has anything to do with physics, but it is definitely there, whether it can be proven or not." — Graham P., student

The opening moments of the first day are pivotal in shaping your students’ posture towards you and the class. Will they be open to new possibilities, or will they shrink in a self-protective stance? Will they look forward to the second day, or will they complain about the prospects for your class with their friends?

Here are some guidelines toward making those first few moments count:

1.1 Tell Them Who You Are

1.1 Tell Them Who You Are

Show your students that you are an authentic person, that you care about them, and that you are passionate about what you are teaching

First impressions matter. What you say and do, in those first few minutes, has a powerful effect on your students’ posture towards the class. Your energy level, your enthusiasm for what you teach, and the way you address the class will inform your students about what kind of working relationship they are going to have with you and what kind of experience the class is going to be. They want to know if you are going to bring your whole self into the room, or be so “professional” that you disappear behind the role of teacher and show very little of yourself. Tell them who you are, your interests, your passions, your life outside of school. If you care about the course you are teaching, if you think it is important, if you are passionate about it—show them. As always, a poor first impression—lackluster, boring, bureaucratic, or punitive—will take time and energy to undo. It is important to cultivate the appropriate posture for this moment. You need to convey that you are energetic, clear about your role, firm in your beliefs, and empathetic towards your students. It is no small task to juggle all of this simultaneously, and, like any great athlete knows, visualizing it before it happens is an important part of preparation.

Establish your posture about the use of power

How power is used or shared is the determining factor in whether students will believe that they are part of a community of learners. Students need to know that you are in control of yourself and the class, but that you hold that control lightly and will not brandish it in their faces. How you respond to the inevitable challenges to that control will establish the kind of authority you will have in their minds.

They also need to know that the purpose of governance is to allow us to do our work together, not for you as an individual to exert your control over them. They need, in other words, to know that they are going to be active participants in the structure of the class, not subservient, passive cogs in an educational machine that you are running. Even on the first day, you need to convey that their being responsible is not the same as their being obedient.

How much control a teacher needs in order to be comfortable is an individual preference and depends a great deal on the students you will be dealing with. Their level of maturity and their attitudes about school will determine how much work will be needed to help them grow into willing partners in the learning process.

1.2 Excite Them About Your Class

1.2 Excite Them About Your Class

Sell the class

Why will this be an important, interesting, meaningful class for them? Give them highlights, shocking facts, or thought-provoking ideas that you will be talking about. Pique their interest; make them look forward to tomorrow. Leave them with a cliff-hanger of an idea. Unless they believe the course you are teaching is worthwhile, it will be hard for them to find their internal motivation. That motivation is the wellspring of self-directed learning.

Your enthusiasm for your own class must be genuine, or your students will perceive your lack of authenticity. They are teenagers—it’s what they do. If you are not genuinely enthusiastic about your subject, this calls for some serious soul-searching about the class and your teaching of it.

Convey the message that genuine learning is the purpose for being in this room

Let them know that you intend to challenge the practice of “doing school”, the usual cycle of “memorize/regurgitate on tests/forget” that so often passes for learning. Instead, you want to build a classroom where everyone is successful at truly learning.

Students need something to believe in. Give them a picture of an authentic alternative to their everyday experience of school. What you do and say on the first day will telegraph your priorities. If your intention is to create a community of learners with them, they should know that before they leave the room on the first day.

Here is the message I gave my students at the start of the year:

The purpose of this class is for everyone to learn as much and grow as much as possible. Physics is a wonderful, fascinating subject, but the real subject of this class turns out to be you. Who you are, your strengths and interests, how much you can grow as a learner and a person—that is the real point of this class.

This will require all of us working together. Some of you are good at math, some are good writers, some good test takers, some are good at putting things together. In order for all of us to be as successful as possible, everyone, including me, is going to contribute as much as possible to the good of the group. We will be sharing the wealth a lot in this class. And it turns out that conversational learning, just talking to each other, is the best way to learn for most people, so we’ll be doing a lot of that, too.

Physics is what we’ll be talking about while we are exploring who you are and what you are capable of. I want you to learn how to take ownership of what and how you learn and to develop skills that will be useful for the rest of your lives. You will learn to be be more tenacious, more self-directed, more willing to take chances and learn from your mistakes. You will become a better learner. You will learn to pay attention to the other people in the room, to teach and learn from each other.

And as a result, you will learn much more. Really learn, not just go through the motions, not just cram, regurgitate on a test, and forget, like so many students do.

To do all this, we’re going to need to rethink everything we do in here. I’m going to need your help in constantly challenging old habits and improving how this class operates. You will have a real say in here.

That’s what we’re going to do in this class, and it will only work if we get a critical mass of you to set aside whatever you have thought about school up until now, and do something new and really different.

Establishing and maintaining this common purpose requires persistent effort at the start of the year. Setting aside time every day to focus on community-building sends an explicit message about how important this is.

Give them a preview ofhow the structure of this class will be different (and better) than many of their experiences in school

Be as provocative as you can in revealing how the class will be run. Statements such as “I never want you to do busywork in here”, “You will have real choice in what kind of homework and how much homework you do”, and even “We won’t have any points in this class, so we’ll have to find some other reason to be motivated” can whet their curiosity and get them to look forward to what will happen next.

1.3 Set the Tone

1.3 Set the Tone

Create a non-punitive environment

Make sure that you have as few rules as possible, and that you will be consistent in making sure that everyone lives by them. Every rule should make sense, as should the consequences of breaking them. Rules or consequences that appear arbitrary or mean-spirited to students directly undermine their sense of ownership in the class. The issue of creating and enforcing rules is described in detail in “Creating the Classroom Culture”.

Start learning their names immediately

If you are going to eliminate anonymity, this first step is crucial. One technique is to make a video of every student saying his or her name on the first day. Take the video home and watch it over and over, then astonish your students by showing you’ve learned all their names in a few days. (You can make a joke about what kind of sacrifices you are willing to make for them.) Challenge them to keep up with you.

When you make this video, let the students know that you will show it to them on the last day of school, so that they can see what they looked like. Tell them that they will come to really know everyone else in the course of the year, and that it will be a shock to realize that they strangers to each other back then.

If making a video is impractical, make a seating chart and take some photos. No matter what you do, the effort to learn their names tells them you want to know who they are.

Emphasize the importance of their knowing each other as well. Have them look around the class and recognize that at this moment, each student knows only some of the people in the room—your purpose together is to form a community in which everyone knows everyone.

Inspire confidence

Let them know that you believe every person in the room can be successful. For students who are lacking self-confidence or who describe themselves as “not good at” your subject, let them know there is nothing in this class that they cannot master if they are willing to do a reasonable amount of work.

Make sure your students are active participants, even on the first day

After your introductions, have them do something that gets them out of their chairs. It can be an activity to them get to meet each other, such as the Spotlight Activity or the Treasure Hunt (described below). It can also be an open-ended activity that introduces them and helps them get excited about the course. Emphasize that they will not be passive recipients of received wisdom, but active participants in the learning process.

1.4. The First Day Handout

1.4. The First Day Handout

Don’t give them a first day handout on the first day

Postpone handing out anything for them to read, if you can. Remember, they are being inundated with rules and grading schemes all day long, and after a while it becomes overwhelming and not particularly meaningful for them. If you are required to hand something out, downplay it and tell them you will go over the rules at a later time.

What to convey in the handout

First of all, keep it simple. It should be a page or less. You may need to break it into two pieces—one for guidelines for the course, and a second piece that defines, say, the details of grading process or a specific set of school rules that you are required to hand out to them. Above all, you want to invite them to an exciting experience and give them a sense that this course will be different and more authentic than much of their school experience. If there are aspects of the course that will stoke their curiosity or interest, state them clearly and concisely here.

What not to convey in the handout

Discussing a lengthy list of regulations and the consequences for violating them on the first day conveys exactly the wrong tone. Nailing down the rules you want them to live by can wait a day or two, and should be a meaningful exercise, as described below.

If you believe that learning is more important than the accumulation of points, show it. Don’t tell them right away how they will be getting points from you. Since you will be redefining grades in an unusual way, it will take more than a one-page handout to convey what you want to do, in any case. Promise your students that you will be addressing the issue of grades at a later time, and that your intention is to focus on the learning process instead.

An example

Here is a handout I gave students in my physics classes. I saved discussing it until the second day, and then focussed mainly on some of the logistical points, like the need to bring a spiral notebook to class, and the existence of portfolios for each student. I saved all discussion of the details of the grading system for much later. The description about my philosophy about grades at the bottom of the page was all they needed to know early on in the year.

Part II. The First Week

Introducing the Philosophy,

Creating Community

Part II. The First Week

Introducing the Philosophy,

Creating Community

Spend as much time as you can during the first week of school in discussing your educational philosophy and exploring how it will be realized in your classroom. Tell your students why your class will be what it is and how and why it will be different than most traditional classes.

You may have doubts about spending much time doing this work, or you may be feeling curricular pressure to get started immediately on covering the material. Remember that these activities are an investment in student participation that will be repaid for the rest of the year in their increased engagement and sense of commitment. You are laying the groundwork for student buy-in. It is only the beginning of a long, ongoing conversation, but it is critically important.

At the beginning, it is essential to simply and clearly articulate the basic beliefs that shape the classroom structures you will be introducing. Your students need to know why they are doing something new. It takes time and energy to get them “on board” philosophically. They need to come to understand that you are intent on establishing a community of self-directed learners and that their roles in that community are going to be different than what they have typically experienced in school.

Getting a critical mass of students to actively agree with the philosophy is a prerequisite to a smoothly functioning class. How much effort and time must go into that effort will depend on how ready your students are to take the leap with you. The more mature and less cynical they are about school, the easier it will be to get to consensus about beliefs. Do not assume that “better” students will agree more quickly than students who struggle in school. In my experience, that is often not the case, because students who are more successful academically are more accustomed to and dependent on being motivated by grades. They have learned how to game the system, and they don’t necessarily want you to change the rules.

For stories about how I implemented many of these strategies in my classroom, see “Finding Meaning” in the book “This Changes Everything”.

2.1 Discussing Working Assumptions

2.1 Discussing Working Assumptions

Articulating your beliefs

I highly recommend creating a list of basic working assumptions that define your beliefs about what school should be. Creating this list can serve the purpose of refining your own understanding of your job. It also serves as a powerful springboard for conversations with your students about what you will try to accomplish together.

Define your working assumptions in language that your students can understand. Your words should challenge them to grapple with those ideas and help them to see whether they share your beliefs about school. Coming to a consensus about these ideas is the starting point for building the classroom culture.

Your goal is to break through the unexamined beliefs underlying doing school and get your students to understand why they need to replace it with genuine learning. Breaking their well-established habits will be a long and difficult process. You want to kick-start that process in a powerful way right from the beginning.

An example

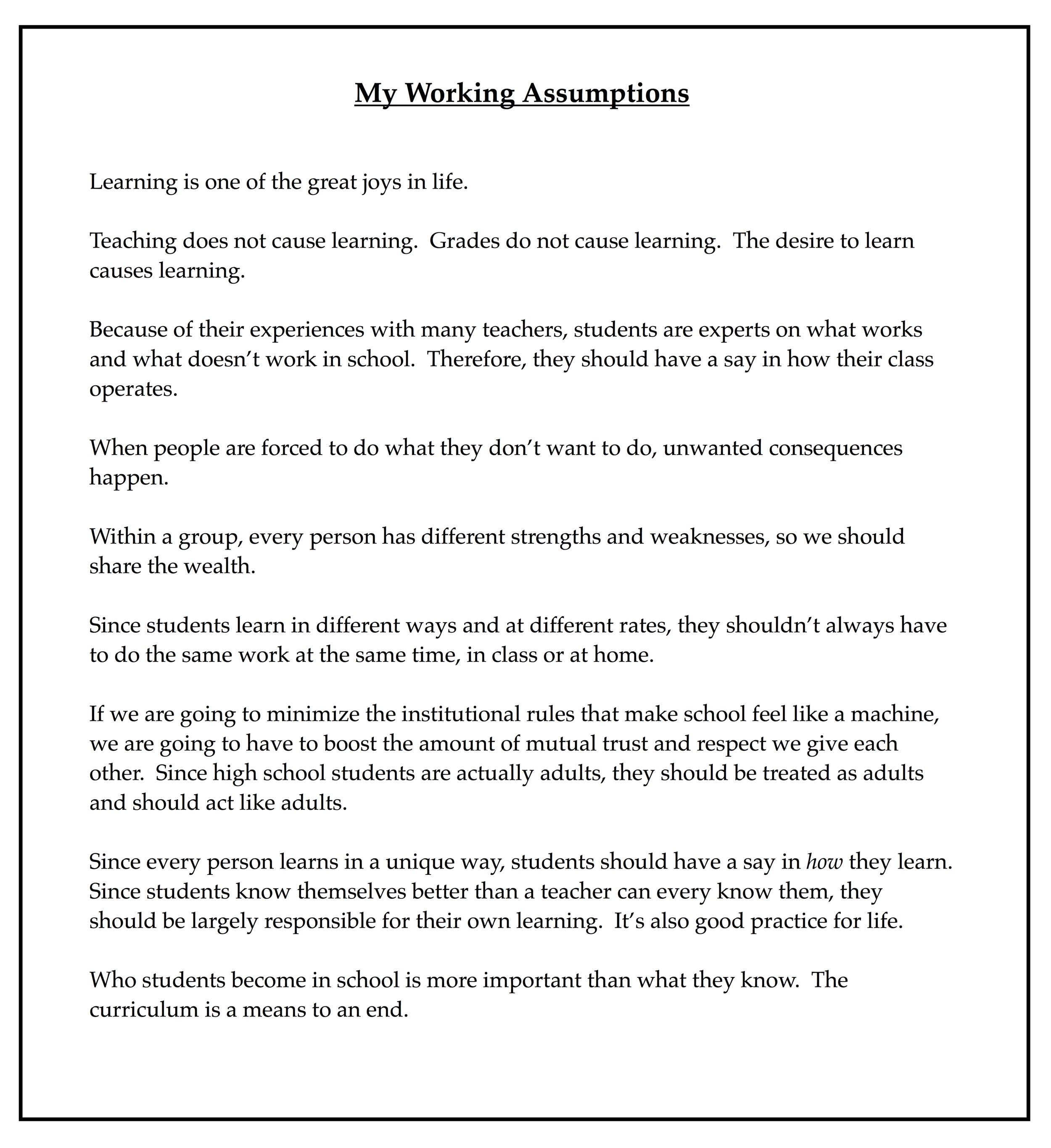

Here is a list of working assumptions I handed out to my students. I found this to be very useful in launching conversations with them about the nature of school, what they thought was working and what was not. Feel free to use my list as a springboard for your own. I would recommend reading it, then putting it away and writing down your own.

After getting students into small groups (four or five), I handed out this sheet and encouraged them to go through it one statement at a time. Their job was to decide which assumptions they agreed with, and which they disagreed with. I also asked them to decide on the most important assumption, the one with the most potential impact.

After giving them 15 or 20 minutes to talk it over, I would bring them back to a whole group discussion and have one group at a time say what they thought was important and why. This led to many discussions around the nature of school, how students are treated, whether they can be trusted, whether school is really about learning, and so forth. Above all, it allowed me to express my posture towards school and what I wanted to accomplish as a teacher. It also led to more clarity about the nature of the classroom culture I wanted to create.

2.2 Establishing the Primacy of Genuine Learning

2.2 Establishing the Primacy of Genuine Learning

The conversations that start with “My Working Assumptions” can launch your students’ understanding of the philosophy of the class. Before they can come to accept that philosophy as their own, however, they must confront the counterproductive beliefs about school that they have developed over many years. Part of the first week’s conversations require taking on those beliefs.

Directly challenge the habits and underlying beliefs of doing school

Your job is to dismantle the traditional assumptions about the roles of teacher and student and, in particular, the use of grades as a motivator. This is a huge leap for many students, and it will take time and tenacity. The main thing is that they begin to trust you and the direction you are taking.

A central and ongoing theme must be the corrosive effect of grades on the learning process. Explore the difference between how students learn something that they want to know (like becoming proficient at a sport or using a camera or using a new smart phone app) and how they learn curriculum in most of their classes when they are earning grades. The difference between internal and external motivation is obvious to most students when seen in this light.

They have been doing school for many years. Your goal is to help them see how little real value that behavior has, and how you will be working with them to create a much better, more meaningful alternative. In my experience, when students talk about the futility of the busywork and lack of meaningful learning, they are generally quite candid. They understand the limitations of doing school—they just don’t know that there is any alternative. If the first week is effective, the experience of exploring these ideas should be exhilarating, even shocking, for many students.

In my own classroom, I found the following sequence useful as an organizing principle for this discussion. As your own conversation about classroom culture unfolds between you and your students, keep this sequence in mind. Ideally, these ideas will build on one another:

Define genuine learning

Students need to see that genuine learning, as defined in ”A New Direction”, is an authentic replacement for doing school. The idea that they will actually learn and retain ideas comes as a revelation to many students. But equally important is the understanding that genuine learning is more than just internalizing the curriculum; it entails their personal growth as well.

The importance of character

Establish that who your students become in class is at least as important as the curriculum they are learning. Explain that the structures used in this class are designed to cultivate character traits that will make students more effective in school and in life. These traits include self-directedness, curiosity, grit, self-awareness, and the willingness to take risks and learn from mistakes. Be clear that these attributes are the heart of living a full, productive and meaningful life in school and beyond. In other words, students are here to learn about themselves.

Define the purpose of your class

Any community needs a common purpose to bind it together. Once students begin to understand the nature of genuine learning, it is time to show them that everything that is done in your classroom is based on a central rule:

“Our common purpose is for every one of us to learn as much and grow as much as possible. Everything we do in this room is based on that purpose”.

This is the one rule that lies underneath all other rules. It is the highest priority, and the criterion for making all major decisions. I call it the Prime Directive, but of course that allusion to Star Trek may or may not resonate with your students. The statement itself can be reformulated any way that is appropriate for you and for them.

Give students an example or two to show how the Prime Directive plays out in the classroom. For instance, the idea of doing extra credit for points, if that work doesn’t help them to learn anything, violates the Prime Directive. In fact, abandoning points altogether can be justified in this way. Similarly, reviewing a completed test more than a week or so after taking it in order to raise the test score is also an ineffective learning tool and therefore also violates the Prime Directive.

A corollary to the Prime Directive also serves as the basis of all behavior management issues.

“No one has the right to interfere with anyone else’s learning.”

When there are issues that arise out of a student’s inappropriate behavior, the issue is not personal — they simply cannot violate the basic purpose of being in the room.

As you can see, the Prime Directive is a statement about the group itself—a way for students to think about about who they are as members of a greater whole. The Prime Directive is worth repeating consistently throughout the year. It helps reinforce the sense of belonging and caring for the good of the group.

2.3 Building a Community of Learners

2.3 Building a Community of Learners

Two models

Like almost everyone who is involved in schools, students have come to believe in what I call the Curriculum Transfer Model of school. This mindset is based on the notion that the purpose of school is to make sure every student learns the curriculum of every course as completely as possible. This approachcan be summarized succinctly in this diagram.

The consequences to this way of viewing school are serious. Because of the primacy of the curriculum, the teacher’s role is basically defined as being a conduit of the content of his course, and the student’s role is to absorb that content as effectively as possible. Perhaps most troubling aspect of this view , however, is that it forces students into a largely passive role of absorbing a vast quantity of information.

A much better approach is to engage students by creating a community of learners with them. In this scenario, they are active participants pursuing a common purpose. This approach is represented by this diagram.

This model starts with the premise that the purpose of school is to prepare students to lead productive, engaged, and satisfying lives. Here, the curriculum serves the purpose of helping students become responsible, capable adults; it is the topic of conversation as we learn from each other and learn about ourselves. It is through the interactions, the teaching and learning that students do with each other, that they can practice the desired attributes such as tenacity, self-directedness, and the ability to work well with each other. Being active members of such a community provides the sense of belonging and meaning that students (like all people) need.

Using these two diagrams to discuss these topics can be powerful tool in establishing the desired classroom culture. Both of these models are explored in detail in “A New Direction”.

In addition to establishing the philosophy of the class, there are a number of tasks necessary for creating the desired sense of community. They include the following.

Eliminating anonymity

As stated earlier, it is helpful to learn your students’ names and have them learn each other’s names right away. Making time to focus on having them get to know each other sends an explicit message about how important this is. Spend a little time every day for the first week or two doing activities that reinforce this goal. Some activities that are useful in this regard are described in detail below.

Early on, create as many opportunities as possible for them to work in small groups. Make sure that who they are working with is randomized, and that they introduce themselves with every new combination. Emphasize that they should be paying attention to who they work well with so that they can choose wisely when permanent study groups are established.

Establish a sense of trust amongst the students and between the students and yourself

Make time at the beginning of the year for students to get comfortable with the idea that they are not competing with each other—that they are, instead, all the learning process together. That means they have to be able to share their failures as well as their successes openly with each other.

Part of trusting is knowing each other. Students want to know who you are not just as a teacher, but as a whole person. Share as much of your life, your hobbies, and your personal history with them as you are comfortable doing. Play Ask Me Anything with them; set a time limit and tell them they can ask you anything about yourself, the subject you teach, or your understanding of the wider world. (You can insist on the caveat that anything which is inappropriate, illegal or simply too personal is off the table.) As members of a community, you want them to bring their whole person into the room, not just the slice of who they are as a Spanish student or an Algebra student. One of the best ways to get them to do that is to do it yourself first.

Have them experience self-governance

Part of the culture you are striving for entails having students become active participants in the functioning of the class. A good way for them to experience what that feels like is to play some games at the start of the year. Getting them outdoors, if at all possible, breaks the hold of the four classroom walls on their imagination. Giving them open-ended problems to work on as teams forces them to invent their own approach to solutions. Several activities that serve this purpose well are the Blind Polygon, Names in the Air, and the Fastest Drop, described below. You can also read about how my students experienced these activities in "Finding Meaning".

Once students have experienced these activities, they are able to viscerally understand the difference between what it feels like to engage in self-governed problem-solving, rather than activities where they are being told how to solve problems.

2.4 Hopes and Fears

2.4 Hopes and Fears

I recommend having your students write you a letter in the first few days of class, consisting of two parts. The first asks them to express their experience of school in general and their sense of how well they have fared in previous classes in your discipline. The second is to write about what their concerns are about your class and what they hope will happen. It is essential that they understand this is not for a grade.

This exercise serves several important functions. It requires them to be metacognitive about their experience in your class right from the start. It also gives you an immediate glimpse into your students’ minds.

Here is the handout on this topic that I gave my students during the first week of class:

There is also a longer-term purpose that your students should be aware of as they are writing it. Tell them that at the end of the year you will hand their letters back to them. At that time, they will write a reflective letter about how they have changed as people and as learners in the course of the year, and whether their hopes or their fears have been realized. These letters are often powerful, poignant statements, and help students realize how much they have grown.

Here is the handout I used to define my students’ writing at the end of the year:

2.5 Dismantling the Bell Curve

2.5 Dismantling the Bell Curve

Drawing a grade distribution bell curve on the board and discussing what it means and how it affects students is the starting point of another important conversation.

The moral imperative

The bell curve approach to school does untold damage to students, particularly those who are unsuccessful. Taking a test, getting a bell curve distribution of grades, reviewing the test and moving on, leaving the wreckage behind, is standard operating procedure in most traditional classes. Discussing this issue is a powerful argument to promote the common purpose of the class. Pursuing the goal of everyone being successful at genuine learning becomes a meaningful alternative to that damage.

Sharing the wealth

One of the antidotes to the bell curve is to have lots of teaching and learning going on in the room. Conversational learning, which occurs in study groups, is the principle mechanism for this kind of decentralized teaching.

Introducing differentiated learning

The other antidote to the bell curve is to make sure every student is working at a level of challenge that is appropriate to him. Use the comfort zone discussion found in ”Differentiated Learning” to illustrate the need to individualize the learning process. The basic diagram is repeated here for convenience:

2.6 The Fundamentals Checkup

2.6 The Fundamentals Checkup

Are they ready?

Students often walk into a class without the knowledge or skills they were supposed to have learned in a previous class, such as the basic algebra skills needed in a physics class. They will rarely admit to these deficits at the start of the year—they may not even be aware of them—but missing these skills can create serious barriers to success.

Once your class is in motion, students might try to fake their way through the first few tests, but as the complexity of your class increases, that will no longer be possible. As in the case of illiteracy, students will often experience too much shame to address their deficits openly. Many students will begin to develop evasive coping mechanisms to hide their failures. Some will be in the panic zone from the first week of school onward.

It is essential that you don’t introduce the content of your class until you know how prepared your students are. To that end, it is necessary to assess their fundamental skills and knowledge immediately.

Activating prior knowledge

Before actually assessing how much they remember, have them do an activity that allows them to explore the fundamentals without any pressure. This should preferably be a socially active event, with lots of conversation going on to see whether the various skills and knowledge are retrievable.

There are several steps to creating an effective warm-up activity:

- Determine what skills and knowledge are truly essential, particularly at the start of the year. You may want to include a little of the initial content in your class to see how many already know it.

- Create just enough problems or activities for a student to show their level of proficiency. Keep it light - if it can be done in three problems, don’t give them four.

- Get them into small (say two or three person) groups. This is one situation where working with people they know may well make sense, in which case they should decide for themselves.

- Remind them that you aren’t even going to look at their work on this activity, so just getting the right answer is of no use to them or to you. Having one person in a group do the work and others copy it over is a waste of everyone’s time. In order for this activity to work, each person has to do the work himself. If a student knows how to do it, he should help someone who doesn’t. If a person doesn’t know how to do it, he should ask questions to figure it out. (“If you don’t know, learn. If you do know, teach”).

- Limit the time they have to do the activity. A little pressure will motivate them work with each other more intensely. Of course, too much pressure is counterproductive, and if they need more time as a group, give them an extension.

- Create stations, if possible, so that they have to get up and physically move around. Post-its on the wall can serve this function. Each station should be a stand-alone activity so that they can move from task to task independently without further instructions.

- Create a form to guide them through the various stations and give them a place to do their work. Here is the form I used:

- Create an answer key so they can check their answers when the activity is done.

Introducing the Fundamentals Checkup to Your Students

Before actually giving them the checkup, it is critically important to make it clear to them that this is not a “test” and that it will not be graded. It is strictly for feedback to see what fundamentals, if any, they need to practice in order to be successful in your class.

Beyond not being for a grade, however, there is a deeper message they need to hear. This is an opportunity to put a number of important philosophical ideas into immediate practice.

- Learning can be a social event that is fun. By activating prior knowledge in an animated, social way with lots of conversational learning going on, they are experiencing the idea that socializing and learning are not always mutually exclusive.

- Students don’t need grades to do the best that they can.

- There is no shame in doing badly on an assessment, because you can fix it. The checkup is telling you what you haven’t learned yet.

- Taking a test is just part of the learning process. It gives you feedback on how to decide what to do next.

- We don’t all need to do the same thing at the same time. If you need to practice fundamental skills, you will be able to, but if you have already mastered them, practicing them again would be busywork, and we don’t do busywork in this class.

Here’s how I would introduce the checkup to my students:

"How many of you have done well on a test, only to forget the material a week or two later? That pattern is part of doing school, and we will be working to replace that in this class. But you’ve probably forgotten some of the basics you learned in your math and science classes that you need to be successful in here. If that’s the case, let’s find out right away so you can finally, really learn it. Even if you have already learned it, you will probably need to refresh your memory since you haven’t used it in a while.

The good news is that no matter what your experiences in your math classes, everyone in this room can master all the algebra you need to be successful in this class. If you have trouble with it, you will be supported and you’ll be able to practice as much as you need. If you’re willing to do the work, you can definitely master the necessary math skills.

Today, you’re going to play around with a set of stations to see if you can remember something about the metric system and using graphs and working with algebra. It’s a no-pressure situation—just go from station to station, talk to your partners, help each other out and see how much you can remember. It should be fun.

Tomorrow, I’ll ask you to show how much of this same material you can do by yourself. If you can’t remember it, don’t worry about it—those of you who need practice will start working on these skills right away, and we’ll keep at it until everyone can do them. There’s nothing here that every person in this room can’t master. This isn’t a test—there won’t be a grade—it’s just feedback to see who needs practice and who doesn’t.

By the way, that’s one of the things about this class—you won’t keep practicing something unless you need to. I don’t want anyone to do busywork ever. So if you can show that you know the fundamentals, you’re done."

If you haven’t already done so, this is an excellent time to give your students the “Merit Badge” analogy. See “Making Tests Meaningful” for more on that.

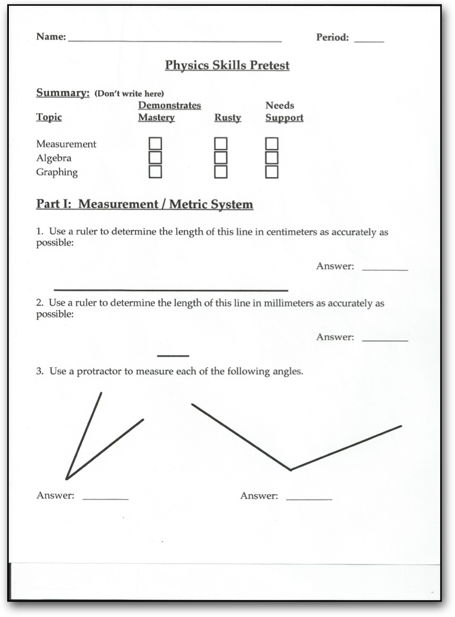

In my physics class, I had students work through a station lab (a series of stand-alone activities scattered around the room) that allowed them to practice the fundamental skills. The first station looked like this:

The Fundamentals Checkup

Here are some guidelines for writing the assessment:

- The check-up should occur within a day or two of the Activating Prior Knowledge activity. If students can keep the fundamentals in their heads for that short a time, they are probably within striking distance of actually learning them when it is time to use that knowledge.

- The check-up itself should be as simple as it can be. Again, only ask the minimum number of questions that will reveal proficiency.

- The assessment should only cover the skills and knowledge that students have practiced in the Activating Prior Knowledge activity. There should not be any surprises in terms of what is being asked or how challenging the level of questions is.

- Group the foundational skills into a few simple categories. This will make it easier to communicate to each student the areas of his strengths and weaknesses. I grouped my fundamentals into Measurement, which included using the metric system, prefixes like “centi-” and “kilo-”, measuring lengths and angles, and scientific notation, Algebra, which included using simple equations and solving for an unknown, and Graphing, which included creating and reading graphs.

Feedback

Once students have taken the checkup, it will be marked up to indicate where the student is proficient and where he isn’t. I recommend not using points, but rather a simple set of marks indicating correct or incorrect.

Don’t total the number of correct responses. Instead of a score or a grade at the top of the first page, each group of skills is given a status report. In my example, I would check a box for “Demonstrates Mastery” if a student got nearly everything right, “Rusty” if he made some mistakes, especially if it looked like a little work would get him up to speed, or “Needs Support” if he showed a serious lack of proficiency. You can also use a simple “Stoplight” system—green means you keep going, yellow means slow down and pay attention, red means stop, you need to do more work.

In any case, students with “Rusty” status can decide for themselves whether they think they can pick up the skill by doing it in class, whereas students in the “Needs Support” category should start working on the fundamental knowledge or skill immediately.

Here is the first page of the skills checkup I gave my physics students, with the evaluation system at the top of the page:

Follow-through

Once a student realizes he needs to learn (or relearn) a fundamental skill, it is important for him to get started immediately. His options for review should be made clear right away, and a plan for working on them should be developed.

This may entail an early conversation with the student to determine what the best way to learn the material would be for him. But it can also be handled by handing him a quick questionnaire that offers options. These might include meeting with you outside of class, meeting with a peer tutor, working in a study center if your school has one, or any other venue of support. This is an excellent opportunity to use these resources effectively, since you and your student have identified what specific skills he needs to work on, and you will be generating the tools necessary for his remediation.

Another tool for students is to include review items in every contract. For instance, in my physics contracts, there was always an “algebra review problem set”, so that a student could practice rearranging the equations of that unit in every possible permutation.

Once you know what your students’ weaknesses are, which fundamental skills and what knowledge they need to work on, you can build a review into every differentiated learning opportunity. Make it clear that you are going to be tenacious in providing opportunities to continue until all students are proficient, and that there is nothing wrong with continuing to work on these skills for weeks or even months, if necessary.

2.7 Other Considerations for the First Week

2.7 Other Considerations for the First Week

If you are using any journals and/or portfolios, this first week is an optimal time for introducing them and how they will be used.

Learning journals

The first few assignments students do will probably be on loose-leaf paper for ease of grading and feedback, but after that, all of their original work—class notes, homework, classroom activities, etc—are best written in their journals. They need to get used to the idea of bringing them to class every day.

Portfolios

Although there will be little to put in them initially, the portfolios should be created early on so that there is a repository for all the students’ work. They need to take charge of their own portfolios, keeping them complete and in good order. More on the use of journals and portfolios in “The Role of Student Work”.

The Rules

In addition to the use of journals and portfolios, the process of creating the ground rules for the class should happen promptly, both to have guidelines for behavior and to reinforce the primacy of genuine learning as the ground for all decisions. More on rule-making in ”Creating the Classroom Culture”.

Part III: The First Month

Introducing the Structure

Part III: The First Month

Introducing the Structure

In general, it will take several weeks to introduce the various strategies and activities needed for a smooth-running community of learners. The pace and the sequence of those introductions are important factors in how well the classroom culture will take root. Here are some guidelines on how to roll them out.

3.1 The Pace of Change

3.1 The Pace of Change

Prior experience

If your students have already been exposed to learning contracts or other structures described in this book, they will need little training or encouragement to use them again. At most, you will need to teach them how you have adapted the basic principles to your course. While the format of your learning contracts may be quite different than the ones a student used in his algebra class last year, for instance, he will have little difficulty in seeing how differentiated learning is structured in your class and adapting to it.

If, however, some of your students have experienced these structures and some haven’t, it provides an opportunity to “share the wealth” immediately. You can create temporary study groups with a mix of both. Every time a new structure is unveiled, students can work on using it together in these groups.

Avoid the “Ton of Bricks” syndrome

No matter what the prior experience of your students, a structure that supports self-directed learning should be unveiled methodically and at a pace that they can absorb. That pace will be determined, to a large extent, by who your students are, how mature and ready to take on the responsibilities they are, and by your readiness to change what you do as a teacher.

Reveal the structure gradually, with time for students to digest how each part works before moving on. While students are quite used to dealing with variations in the rules and structures they may encounter in each teacher's classroom at the start of the year, what you are presenting to them may well represent a fundamental break from their prior experiences. It is important to put each structure into practice individually, with time for your students to get proficient at it, before moving on to the next structure. Since many structures, such as homework and tests, are being used for new purposes, time must be taken to make sure that students can see those purposes clearly and buy into the philosophy behind them.

Being cautious in the pace of introductions is especially important if you are using these structures for the first time yourself. As always, you should pay close attention to how well each structure is working and adjust and adapt as needed. Juggling too many new structures at the same time will be confusing and counterproductive for you as well as for your students. If you or they are feeling overwhelmed, slow down. In this case, reread the section on working in the comfort zone, as described in “Learning Contracts”, for more on this subject. Remember, you have to be comfortable, too. Exploring these ideas should ideally be exciting, but not a source of panic.

Start where your students are, not where they should be

It is tempting to design the first unit of the year based on the first chapter in the textbook or on what you did at the start of last year. Regardless of the course syllabus, however, your job is to respond to the real needs of the real students in the room.

The results of the Fundamentals Checkup will tell you directly how many of your students are lacking prerequisite skills. If there are only a few, work intensively with them and provide them with the support they need. If a significant number of students are lacking those skills, however, ignoring that deficit and moving on to what the first unit “should” be is an exercise in magical thinking and will cause considerable damage.

First, it immediately puts a critical mass of students in the panic zone—too much challenge for their level of expertise. This impedes their learning from the start of the course. Second, it sets exactly the wrong tone; it telegraphs the message that covering the curriculum is a higher priority for you than whether your students will actually learn that material. An extreme example of this approach was provided by a teacher I know who, on the first day of school, handed out the homework assignments for the entire first semester. The message to his students was clear: The train is leaving the station whether you are on board or not.

It is far better, now that you know how ready your students are, to begin your coarse there, where they are. Working with reality is simply more effective than working with the waythings ought to be.

What is the shape of your bell curve?

Perhaps your students’ readiness and motivation to learn are distributed along the classic bell curve.

On the other hand, if you are teaching an “honors” course, it might be skewed towards the top.

A “Level One” or “Remedial” (or whatever name your school gives the lowest track) course may be skewed downward.

If your school is “detracked”, the distribution curve may be the standard bell curve on steroids,

or even the dumbbell distribution.

All of these shapes directly affect the scaffolding you build around the needs of your students. A wide distribution range requires a shorter introduction to new material before launching into differentiated learning with a wider range of challenge available -- more remedial and practice options for the struggling students, and more sophisticated enrichment activities for the ones who pick up the material quickly.

A profile with several bulges and a gap may make “sharing the wealth” more complicated and/or more important. This may require redesigning study groups so that conversational learning occurs in two different domains, one that works on fundamentals, and another that focusses on enrichment. Obviously, care must be taken not to create a situation that reinforces racial stereotypes or has the appearance of structural racism. Another approach might be to have teacher-led workshops for practicing fundamentals and several independent study groups that can simultaneously explore enrichment activities.

No matter what the shape of the distribution, the structures you design must always be responsive to the learning and psychological needs of your students.

3.2 The Sequence of Introductions: Planning the First Month and Beyond

3.2 The Sequence of Introductions: Planning the First Month and Beyond

Plan backwards to create the sequence for revealing the structure

Decide what classroom structures are essential for students to know immediately and how you will reveal them to the class. Issues that students will be curious about might include how homework is done, how classroom activities (labs, language labs, study groups) will be organized, what contracts will look like, how they will self-assess their own work, how their work will be organized (journals and portfolios, for example), how they recover from doing badly on a test, and so on.

I found the following sequence useful in my classes. Some of these structures may be irrelevant to your needs, and, of course, you may implement techniques not included here. You may also find that a different sequence is appropriate for your students, or for you as a teacher. The main thing is to pace these introductions so that every student can master each one before adding the next.

I have included only a minimal description of how to introduce each structure, since every topic listed below is explored much more thoroughly in the individual chapters dedicated to each of these structures. You may only be using a few of these structures, and may need to decide for yourself what the sequence of introductions should be.

Each structure has its own central focus: a desired character trait that the structure itself is designed to reinforce. Each character trait is listed below as well.

Repurposing student work

In essence, this is a question of teaching students how to learn more effectively. When rethinking the uses of classwork and homework, the focus should be on cultivating the student attributes of metacognition and grit.

Student self-evaluation

As described in ”The Role of Student Work”, you should introduce each piece of the contract structure separately, and explore how it will be evaluated thoroughly before moving on to the next. For every distinct type of activity (homework, classroom activities, class notes, worksheets, etc.), you should have a checklist and a rubric that describes what excellent work should look like and how work will be evaluated. The focus of self-evaluation is the attributes of responsibility and independence.

Study groups

Creating functional study groups and emphasizing the importance of conversational learning is pivotal in the creation of the classroom culture. The focus, while creating them, is on the attributes of social skills, such as leadership, compassion, and being aware of and concerned with the good of the group.

Formative assessments

At the time of the first quiz or test, help students rethink the purpose of assessments. Remind them that they aren’t done learning until they have mastered what they got wrong on the assessment. The focus here is on the attributes of courage and tenacity.

Minicontracts

Introducing student choice and true differentiated learning is at the heart of everything you are trying to do. This introduction needs to be done at a pace that can be absorbed by all your students. The focus is on the attributes of responsible behavior, making good choices, and self-directedness.

Unit contracts

If you “graduate” to the full structure of unit contracts, the focus will be on the student attributes of responsibility and time management.

Redefining grades

Helping students rethink their understanding of grades will happen at a number of levels, scattered throughout the year. As described above, the role of self-evaluation will be explored in the first few pieces student work. If you choose to eliminate the use of points in your class (which I highly recommend), alternative forms of assessment should be explored by the end of the first contract. Students who are preoccupied with their grades will be relieved that there is a fair system in place. The self-grading of mini- and unit contracts is another skill that has to be practiced. And finally, at the end of the first marking period you will need to address grade conferences and the use of portfolios to negotiate a quarter or semester grade.

The focus here is on the attributes of internalizing motivation and rethinking the working relationship between teacher and student.

3.3 Community and Trust Building Activities

3.3 Community and Trust Building Activities

It is beyond the scope of this book to explore the endless options for introducing students to each other and for building a sense of community and trust. However, I want to share a few activities that I have found useful at the start of the year:

The Name Game

At the start of every day during the first week or two, ask if anyone can name every other student in the room. If no one volunteers, have every person say their name and ask again. Remind students to focus only on the people they don’t know yet. At first, only ask them for first names, and make sure everyone sits in the same seat every day.

Especially at first, applaud a student’s courage for trying. If they get stuck, allow them to ask another student for help. Once one student has named everyone, ask for a second volunteer, but have them do it in a different order—say starting at a different side of the room. See if he can do it faster. Use a stopwatch to add a competitive edge to it.

After nearly every person is successful (it might take a week or two), give them a seating chart quiz (obviously not for a grade). Have them fill in as many names as they can on a blank seating chart. Then have someone play the name game again to fill in the holes. Once they have done that, they have to put the chart away before playing the game again. If they want to “cheat” and study the seating chart before playing again, so much the better.

Treasure Hunt

This is a quick, easy activity that can be inserted at any point during the first week of school when a change of pace is needed. If there is time, this can even be done on the first day of school.

Every student is given a list of statements like the one below. As quickly as possible, every student must find another student for whom a statement is true and write his name next to that statement. Since their goal is to get to know everyone in the room, encourage them to start with people they haven’t met yet.

Spotlight Activity

Unlike the Name Game, which can be played every day for a week or so, the Spotlight Activity is done only once. It is an energetic, exciting and very effective way to have students get to know each other better.

Have every student get out a piece of paper and number down the left side of the page the number of students in the room. The task is for every student to talk to every other student and exchange one fact with him. The hard part is that no one can say the same fact about himself twice. That means if there are 24 students in the room, everyperson has to say 23 different statements about himself. Many students will struggle to think up that many items. Give them examples before they start. They can use trips they have taken, facts about their household—number of siblings, their pets, how many TVs or phones they have—likes and dislikes about food, movies, music, sports teams, hobbies, broken bones, scars, sports they play, and so forth.

This exercise can be somewhat chaotic and with a large class can take quite a while. You can always stop it at any point by giving a two-minute warning. Students don’t have to talk to every other student for the activity to work.

In phase two, put the “spotlight” on one person at a time by holding your hand over his head. Other students then call out what they know about him in no particular order, always starting with his name. “Henry has two brothers”, “Henry went to Disneyland last summer”, and so forth. The constant repetition of his name, combined with the collection of facts that everyone learns, helps ground the learning of who everyone is in the room.

It’s important for you to participate fully in this activity as well. It is a prime opportunity to let your students know you are a whole human being with a life outside of school and interests and hobbies of your own. Make sure that you put the spotlight on yourself at some point in the middle of the process.

Two Word Game

This activity is especially good for disciplines such as science, where there are patterns to be learned. Tell students that they have to listen to a number of statements and see if they get the rule that governs what you are saying. If they think they get it, they need to test their hypothesis by making up their own statement and seeing if it is true.

You might start the game by saying, “It’s green, but not brown. It’s mommy, but not mother. It’s daddy, but not father. It’s bathroom, but not kitchen.”

A student may think he understands what the rule is and may test it by saying, “It’s sis, but not sister”, in which case you would tell him that that is not correct. (Do you see the pattern?)

After a while, some students will know the rule and others will not. In my class, I would tell students that this is what knowing physics is like—you see the patterns and understand why the world works like it does, and those poor souls who don’t get it have to lead a frustrating life where things don’t make sense. (By the way, the rule is that the correct words all have double letters.)

Four on a Couch

(Thanks to Gina Hubbard of Palatine High School).

This game requires all students in the class to participate. Each student should know the names of the others in the class. If it is early in the year, you can leave a list of first names on the board to refer to while playing the game.

Preparation:

Write each person’s name on a slip of paper.

Arrange desks in a circle with one extra desk included. Designate 4 of the desks at one part of the circle to be the “couch”.

Divide the class evenly into 2 easily identified teams. If you don’t have the same number of boys and girls, you can have different color shirts or have those with and without lanyards.

Place students around the circle, alternating teams and leaving one empty desk, just be sure it is not one of the “couch” chairs.

Shuffle the slips of names and hand each person a slip of paper with a name on it. It is OK to have one’s own name. They should not share their new identity with anyone.

To Play:

The object of the game is to seat four of your team members on the couch.

The person to the right of the empty chair begins the game. He or she will call out a name. The person who is holding the slip of paper with that name on it will get up and sit in the empty chair. This creates a new empty chair. The person to the right of that empty spot will call out another name. Once again, the name called will get up and sit in the empty spot. This continues until the “couch” has all 4 spots filled by the same team.

You may not call the same name twice in a row.

The ideal number is about 16 players, but I have played this with up to 26 Calculus students with success. Textbook Treasure Hunt. If you have a textbook, this is a way to familiarize students with it. Create a list of interesting facts that can be found in it. Make sure that finding the page for each fact requires using the index, a glossary, the table of contents, “about the author”, the inside covers or just the physical book itself—how many chapters, how many pages, how much does it weigh (have a scale handy).

Pairing students (randomly, as always) speeds the process up and forces them to solve the problem of how to find each fact together.

Blind Polygon

(Thanks to David Allen of Evanston Township High School).

Materials needed: One blindfold (a 2” by 24” strip of opaque material) for every participant, and a 30 foot length of clothesline or other rope per group of no more than 12 students.

This game needs to be played outdoors. Have the two teams form a group some distance from each other. Layout a rope to one side of each group. It can be laid out in one length or doubled up. Have the students put on blindfolds and tell them their task is to walk to the rope and somehow create an equilateral triangle with every team member touching the rope.

Once they have finished, have them take off their masks and view their triangle. Have them discuss how they could have improved their performance. Then have them return to the original position, reset the rope, and after they have put their blindfolds back on, have them create a square.

If there is time, see if they can repeat the process with other shapes, particularly a circle, to challenge them further.

Names in the Air

Materials needed: A minimum of 8 tennis balls for each group of up to 12 students, one stopwatch.

Start by having the students stand in a circle. Hand a tennis ball to one student to start the pattern. He will throw the ball to another student, calling that person’s name while the ball is in the air. The second student then throws the ball to a third, also calling his name. The trick is that every student must catch and throw the ball exactly once before it is thrown back to the student who started the pattern.

Next, let the first student start the pattern again, but once it is in play, hand him a 2nd ball to throw while the first is in motion. The objective is to have a third, fourth, and fifth ball in motion continuously, with everyone calling names of the people who are catching the ball.

Finally, tell the students to speed the process up as much as possible with as many balls in the air as possible. Total chaos ensues!

The Fastest Drop

Materials needed: 1 tennis ball per group of no more than 12 students, one stopwatch.

This is a natural follow-up to Names in the Air. While students are still standing in a circle, take all the tennis balls back but one. There is just one rule in this game: The ball has to be passed through the same pattern you had in Names in the Air, and each person has to touch the ball in the sequence. The objective is to get the ball through the sequence as quickly as possible.

Once students start, they will quickly try to organize themselves in a way to speed things up. If they ask whether they can change where they are standing, your response is that there is only one rule — everything else is acceptable.

For stories about how these games are experienced, see “The Thrill of Self-Governance” in the chapter “Finding Meaning” of This Changes Everything.

3.4 Activities for Randomizing Working Groups

3.4 Activities for Randomizing Working Groups

Counting off

If you want to create 5 groups, simply start anywhere in the room and count off from 1 to 5 repeatedly until you have assigned every student a number. Then have all the “1’s” meet in one area, all the “2’s” in another, and so on. You can vary the results by changing the pattern of counting; you can start counting from a different seat, skip rows, go back and forth through a seating patter pattern rather than in the same direction, or count every other student. This method has the advantage of automatically taking care of the fact that some groups may have to have four members and some five, for instance.

Silent Sorting by Birthday

Tell students they have to line up along the wall or out in the hall in order of their birthday, with January 1 at one end of the line and December 31 at the other. The only trick is that they cannot speak. Don’t give them any other instructions — they will have to invent a means of communicating on their own. Once they have finished sorting themselves, have them call out their birthdays so everyone can hear it, and make a big deal out of their success even if there are a few glitches. Now you can sort them into groups by taking the first 5 birthdays as one group (if you want groups of 5), the next as the second and so forth. Or you can count off, as described above, down the line. You can also fold the line in half, if you want to create pairs, with the first birthday joining the last birthday.

Silent Sorting by Age

Do the same activity as sorting by birthday, but include the year, not just the day. This is especially appropriate if your class includes students from different years, say Freshmen and Sophomores.

Using Playing Cards

There are many ways to use cards to sort students. If you are sorting them into four groups, sort them by suit, by having an equal number of hearts, spades, clubs and diamonds and distributing them face down. Then have all the hearts meet in one area, clubs in another. If you want more than four groups, mix in cards from another deck. For instance, if you want six groups, make sure you have six aces, six kings, and so forth. Then have all the queens meet in one area, all the jacks in another.

Sorting by Shoes

Have students count the number of holes in their shoes. Define a hole as something that a string can pass through. Therefore, slip-on clogs have no holes, flip flops have two holes, and street shoes have the number of shoelace holes. If two students have the same number of holes, do a secondary sort by the size of the shoe, so shorter shoes with 8 holes would be a “smaller number” than longer shoes with 8 holes.

Clock Buddies

Create a diagram like a clock and have every student put a different name at every hour on the diagram. He can do this by walking around and agreeing with one other student that the two of them will be, say, 2 o’clock buddies. When you want students to partner up for an activity, simply call out “find your 6 o’clock buddy”, making sure you don’t repeat yourself too often. You can also find some way to randomize the process, like having a big clock with a spinner or throwing one or two dice to get a number from 1 to 11. You can also have a student spin the spinner or throw the dice, and make a big deal about what an honor it is to do it.

3.5 Tenets of a New Paradigm

3.5 Tenets of a New Paradigm

First impressions matter

As your students walk into your classroom for the first time, they are looking to see what kind of a person you are, and what kind of an experience they will have in your class. Striking the right tone in the first few minutes of the first class can effectively launch the classroom culture you want to create.

Establishing the appropriate classroom culture is a worthwhile investment in time and energy

Without a foundation of common purpose, marching through the curriculum is much less effective.

Teaching the primacy of genuine learning requires tenacity

Remember, they have spent most of their lives being trained in the Curriculum Transfer Model, and they believe that doing school successfully is their true purpose. The idea that they are here to learn and grow as learners is a radical departure from their experience; they can learn to replace their old habits, but it takes time and effort.

Assessing the skill level of students at the start of the year allows you to respond to their needs immediately

Assuming that all your students know what they “should have learned” in prerequisite courses is a very dangerous practice; all too often, it leads to students feeling overwhelmed and lost from the start of the year. Checking up on their actual knowledge base allows you to attend to their deficits. It also gives you a better sense of how quickly to proceed with the course content.