A recent New York Times article describes a program at Smith College that teaches students how to handle failure well. These students have always been the most successful in their high schools. According to a program leader, "For many of our students -- those who have had to be almost perfect to get accepted into a school like Smith -- failure can be an unfamiliar experience. So when it happens, it can be crippling."

Why is such a program necessary? I would argue that despite (or perhaps because of) their success in school, these students haven't learned this fundamental fact:

Nothing worth learning can be mastered without making mistakes and learning from them.

Whether it's shooting free throws, calculating the path of a projectile, or writing an excellent short story, practice is essential precisely because when we push the envelope, we often stumble, and in stumbling we expose more precisely what we don't know yet.

These days, many people understand the importance of tenacity in the learning process. But the reason why these students are "failure deprived" runs deeper than a lack of grit. Rather, it stems from the fact that school has trained them to be externally motivated, primarily through grades. They believe their value as human beings is locked up in how many points they can accumulate. That’s why, as the article describes, getting a grade less than an “A” can cause a breakdown.

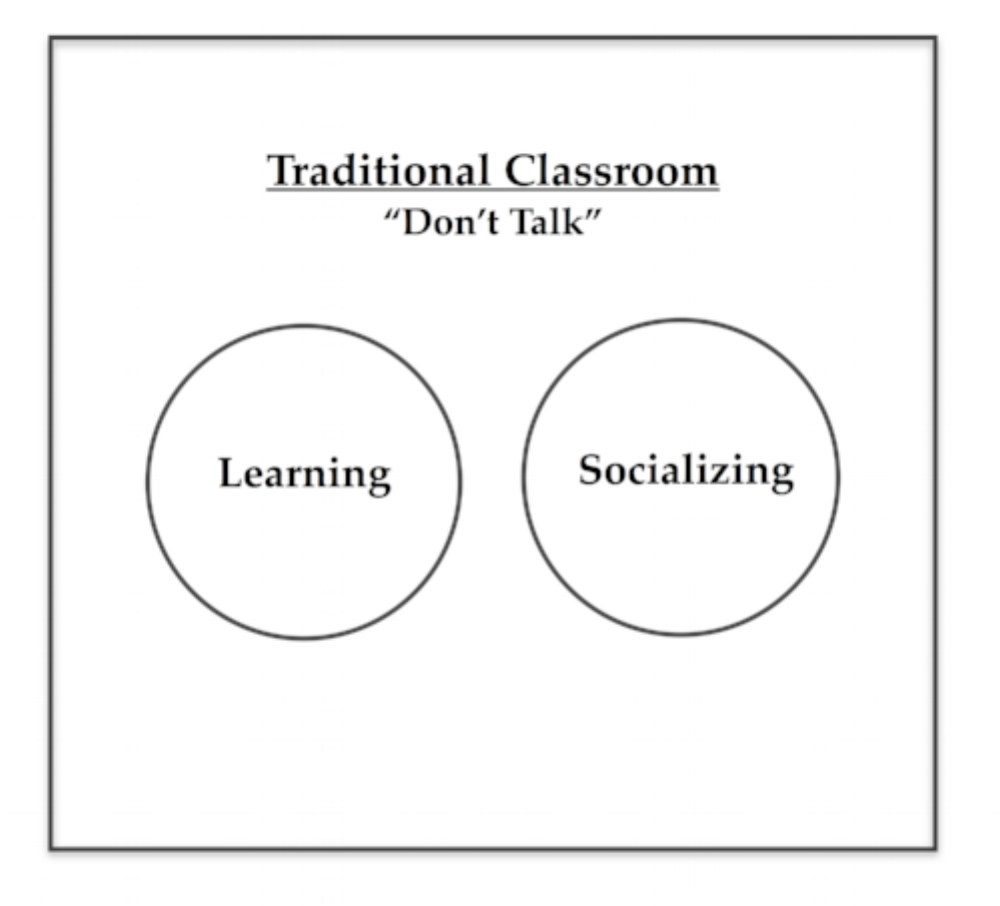

The antidote to this problem is to foster a student’s intrinsic drive to learn and excel. When she is working out of curiosity, and she is working with other students to figure something out together, setbacks are just part of the process. Getting a poor grade on a test is simply feedback that there is something that she hasn’t learned yet.

Transforming a students’ posture toward failure requires reshaping the fundamental structures of the classroom. The work students do, the feedback they are given, the conversations they have, and what happens after they take a test all have to be designed to foster a new attitude about the act of learning. Above all, the classroom culture has to be one in which making mistakes is an expectation, not a black mark.

In other words, the classroom must become a community of self-directed learners. Once that happens, the fear of failure becomes largely irrelevant.