Learning Contracts: The Structure of Self-Directedness

Learning Contracts: The Structure of Self-Directedness

”We’re born to be players, not pawns.” — Daniel Pink

“Any system which cannot or will not adjust to and meet the needs of every individual becomes a destructive system”. — David Aspy and Flora Roebuck

“When students are given the choice to learn, it’s more likely they will want to learn.” — Ashley M., student

Once we understand the importance of differentiated learning, we need to create classroom structures to make it happen. These structures should customize the learning experience of every student. They should respond to each student’s learning needs and provide the scaffolding for students to make good choices. If a student takes longer than her peers to grasp new concepts or learn new skills, she will be able to continue working. If another student has already mastered the material, she will be able to move on to more challenging work.

Giving students this flexibility requires rethinking the nature of homework and classwork. There must be a structure that allows the teacher to introduce new material to the whole class, while also letting each student work at her own pace. What is needed is a learning contract.

In any class, some activities are best done together. However, there are also moments when learning needs to be desynchronized, when the one-size-size-fits all approach needs to be replaced with something that is responsive to the needs of the students. During open work time, where students are doing different things at the same time, a learning contract can clearly define what activities are available so students can make good choices.

Like legal contracts, learning contracts define the working relationship between two parties: the individual student and the teacher. Contracts establish a new level of independence and responsibility for each student and free the teacher from controlling every aspect of the student’s experience.

6.1 A Sample Learning Contract

6.1 A Sample Learning Contract

To show how a learning contract might be used, here is a simple example. In a physics class, the students have been introduced to the concept of conservation of energy. They then take the following ungraded check-up to see whether they have mastered the concept.

Students are given the answers immediately and have a chance to talk to their neighbors about any questions they got wrong. Then they are given the following contract. It requires them to choose any two items from the “Practice” category if they got the check-up wrong, or from the “Above and Beyond” category if they got it right. The “Practice” category includes an exercise that addresses conceptual misunderstandings, a problem set that allows students to practice the problem-solving aspect of the material, and an opportunity to seek help with the teacher outside of class. The Above and Beyond category includes two enriched problem sets that are beyond the scope of material that will be tested (hence the name “Above and Beyond”). It also includes the opportunity to “share the wealth” with students who didn’t do as well on the check-up.

Once students have chosen what work they will do, they are given an open work session of one period. When students have completed the work, they assess themselves on each item they did and turn this in with their work. Self-evaluation is described in detail in the chapter“Grades Reconsidered”.

6.2 The Benefits of Learning Contracts

6.2 The Benefits of Learning Contracts

"The contract system was very successful because not only does it make students more responsible, but it gives them the option to do what they need to do in order to be successful. Since the contract system gives you options on what work you do, busy work is eliminated. All of the work you complete should be useful if you are honest with yourself." — Jared R., student

Contracts promote self-directedness

They provide students with choice and responsibility in steering their own learning process. For many students, the experience of school is one of relentless, enforced passivity. Learning contracts replace that experience with a structure that nurtures self-directedness and engagement. This boosts motivation and class cohesiveness and is a powerful force in creating an effective learning environment.

Long-held and counterproductive habits of doing school are replaced with self-directed learning. When students begin to see themselves as capable, trustworthy people, it can have a powerful effect on them academically and personally. It helps them to better learn the skill of learning.

Contracts can significantly reduce busywork and boredom

If a student is given adequate feedback, she will know when she has mastered the current material. She can then move on to work that is more challenging. Sometimes, however, a student will instead choose to do work that is repetitious or too easy for her because it requires less effort and doesn’t hurt her grade. This is particularly true of students who are still in the thrall of doing school.

If a student chooses instead to do busywork, the teacher will quickly become aware of it. For instance, if a student is doing well on assessments but is continuing to do remedial work, this will call for a teacher-student conversation about whether she is choosing to be bored. It’s no longer possible to for her to blame the teacher - she has made a bad choice, no more and no less. Conversations like these can often be pivotal in helping a student challenge the habit of doing school and become more self-directed.

Discovering that busywork is no longer required undoes a common source of student resentment. Furthermore, when a student learns how to find the right level of challenge and pursue her learning at that level, she becomes a more effective learner.

Contracts provide a mechanism for accommodating different modes of learning

Contracts can include any differentiated items the teacher chooses. For instance, a single learning goal can be addressed through items that are visual, auditory, and tactile-kinesthetic in nature. As students become more aware of their own learning styles, they will become more adept at making good choices about how they learn.

Contracts provide a practical structure for formative assessments

Following a quiz or test, a contract can allow each student to do the specific remediation work that she needs. The quiz or test itself becomes the feedback that drives her choices on the learning contract.

Contracts can be adapted to many situations in a wide range of disciplines

Learning contracts are flexible tools: they can be designed to serve virtually any academic function. Contracts can organize conceptual learning found in the humanities, as well as skills-based learning found in mathematics and science. Similarly, contracts can be adapted to the particular attributes of any group of students. For instance, if a class has immature, less self-directed students, a contract can be designed with more required items and fewer, more narrowly-defined differentiated items. As students become more independent and responsible, more differentiated choices can easily be added.

Contracts give teachers more freedom to work with individuals or small groups of students

Contracts allow for open work time in which students are working independently on different items. As students become more self-directed, open work time provides much-needed opportunities for the teacher to work with students on a smaller scale and respond to their needs more effectively than when working with the whole class. Interactions can range from conversations with individual students to ad hoc workshops with small groups of students who are all struggling with a particular issue.

Open work time reveals much more of the motivations—and successes and failures—of students than can be discerned in a traditional whole-class setting. A student who is disengaged and unmotivated becomes easier to identify, and a desynchronized classroom gives the teacher the freedom to discuss the situation with the student immediately.

Contracts encourage greater creativity in teachers

In a traditional classroom, all the students typically do the same thing at the same time, and the range of ways in which teachers can create new materials is limited. There aren’t many opportunities to develop work that will challenge the brightest students in the room or provide enough remedial work to support the slowest students. The differentiation offered by contracts, however, encourages teachers to become more responsive to the needs of all students. Teachers have more freedom to create a range of curriculum, activities, homework, research projects, and independent work to positively shape the experiences of students who might otherwise be bored or overwhelmed.

Contracts reinforce a growth mindset

All too many students are trapped in a fixed mindset, assuming that if they do badly on a test, for instance, it is because they are not good students and there is nothing that can be done. Contracts, however, are designed to allow individual students to learn from their mistakes and choose a path towards mastery. This actively reinforces the idea that learning comes from effective effort. In other words, contracts train students to adopt a growth mindset, to be less risk-averse, and to accept the notion that learning is a process that requires making mistakes and learning from them.

6.3 The Scope of Learning Contracts

6.3 The Scope of Learning Contracts

Learning contracts are versatile tools. They can be designed in many shapes and sizes. Contracts can range in scope from organizing a choice of activities within a single class period to providing a unified structure for an entire course. They are adaptable to meet the needs of any discipline and any group of students.

For the sake of simplicity, I will define two classes of learning contracts: minicontracts and unit contracts.

Minicontracts are limited in scope and are generally designed to serve a single purpose, such as preparing for a test. They can comprise a span of time from part of a single period to several days and can contain as few as two or three items or as many as a dozen or so for students to work on. The principle function of a minicontract is to provide an opportunity for students to work on different things at the same time, both in the classroom and at home.

Minicontracts can be useful for teachers who are first learning how to integrate student choice into the classroom. For many students, having the freedom to choose what they are working on will be a new experience, and having simple, small-scale contracts is a relatively easy introduction in learning how to make wise choices.

The second class of contracts, unit contracts, are larger, more complex structures that organize all the work done by students within a given unit of study. Unit contracts can serve more functions more comprehensively than minicontracts. They can be used to organize the learning goals of an entire course, to document every student’s entire learning process, and to teach students to self-evaluate their work and be responsible for their own learning.

Creating a set of unit contracts for the first time can seem a daunting task, requiring a significant effort. Not only must all student activities be reorganized, but the classroom culture must be transformed to support student choice. For many teachers, this seems to be too large a change from their accustomed classroom structure.

A more reasonable approach is to plan and use minicontracts to get acclimated to student choice and to explore how that choice can be best utilized. The remainder of this chapter is dedicated to the study of minicontracts. The advantages and challenges of using unit contracts will be discussed in depth in the next chapter.

6.4 When to Use Minicontracts

6.4 When to Use Minicontracts

Minicontracts are useful whenever differentiated learning is required. They may be needed because there is a range of motivation and readiness to learn in the room, because there are different rates at which students are learning, or because there is a bell curve of grades that needs to be addressed. Minicontracts may also be important in addressing how students with different learning styles work on any given topic.

Here are a few examples of circumstances where it would be appropriate to create a minicontract:

Classwork

Students can be given a choice of how to use class time to master a concept has just been introduced. Multiple activities can be made available based on the diverse needs of students. This kind of open work time is described in greater detail below.

Homework

If a new concept or skill has been introduced during class, a checkup at the end of the period will reveal who has mastered the material and who still needs more practice. A simple contract can define a range of homework that will challenge every student appropriately. This could cover one night's homework or could last several days—or longer. A single minicontract can contain both classwork and homework, giving students even more choice and leeway in their individual learning process.

Test preparation

When it's time for students to study for a test or other assessment, contracts can help individualize the review process. As always, feedback from the teacher is important. This feedback could be a review packet or a pretest to help students understand their strengths and weaknesses. The contract can then provide work for them on an individualized basis, aimed specifically at the issues they need to work on.

Exam preparation

For many teachers, this is a natural use of minicontracts, since differentiation can greatly enhance reviewing for an exam. By identifying what each student needs to study to prepare for the exam, the review process can be tailored to her specific needs. Replacing the traditional one-size-fits-all exam review with a differentiated review allows each student to study in a more effective way. This strategy is explored in full in “Making Tests Meaningful”.

Independent research / projects

Contracts can provide structure for research projects. For instance, a calendar of milestones can be built into a contract, with a definition of the tasks to be completed by each milestone as contract items. In a group project, contracts can define each member’s role, including the required work and schedule for each person. Different roles (researcher, writer, video editor, etc.) can have distinct contract items that define the work.

Test remediation

Formative testing requires a structure for remediation so students can learn from their mistakes. Using a minicontract as that structure allows the remediation to be individualized. The test itself can serve as feedback to help students choose appropriate work. Designing a test remediation contract consists of anticipating all the types of mistakes and misunderstandings students might encounter, and compiling a set of contract items that will give them the practice they need to learn from those mistakes. An example of a test remediation contract is given below. The use of formative assessments is explored in depth in “Making Tests Meaningful”.

6.5 A Gallery of Minicontracts

6.5 A Gallery of Minicontracts

Contracts can be adapted to almost any discipline, student body, or activity. Here are a series of contracts written to serve a variety of purposes.

Algebra Quiz Remediation Contract

(Thanks to Esther Song of Niles North High School)

Here is a minicontract that followed an algebra quiz. The teacher had some students who already knew this concept, and others who, even after an introduction, were unable to work with the necessary equations. Let’s look at how she tackled this problem.

In the left-hand column, she listed the work that everyone is required to do. This includes taking the quiz itself and doing several metacognitive exercises. For each problem they got wrong, there is an item for them to work on in the Practice column. If a student did well, they were encouraged to do Above and Beyond items. Notice that there are learning opportunities in a variety of modes, including completing problem sets, working in a help session with the teacher, watching a video, reading in the textbook and/or tutoring another student. Every student was required to do a minimum of four items from the two right-hand columns.

AP Psychology - Differentiation by Learning Style

(Thanks to David Allen of Evanston Township High School.)

This contract gives students a wide array of choices, from hands-on experiments to videos to iPad apps. Students were given one class period plus whatever time they chose to spend at home to do a minimum of three items from the list. Notice that there is a column for students to evaluate the process of doing the work and another to evaluate how well they mastered the material in each activity.

Geometry Contract - Organized by Learning Goal and by Schedule

(Thanks to Vanessa Brechtling of Niles West High School)

Here is a one-week minicontract that focuses on the skill of measuring areas inside a circle.

The first thing on the contract is a list of learning targets. (I’ll call them “learning goals” from now on.) Students can clearly see what they should know and be able to do when they are done with the contract. For contracts of any length, this is useful information for students.

Next, the work is broken into three categories: Whole Class items, which are done together and are required of every student, Needs Practice, which offers remediation, and Above and Beyond, which is enrichment work. Every student is expected to do choose between the Needs Practice and Above and Beyond for each learning goal, depending on how successful they are on a check-up that has tested for their understanding of each learning goal.

At the bottom of this sheet is a calendar that shows when there will be open work time (she calls it an Independent Work Day) and when specific homework is due.

History Contract - Encouraging Independent Work

(Thanks to Rick Cardis of Evanston Township High School)

In this contract, only five items are required, including two optional items. Notice that in the Above and Beyond section there are options for students to “be creative” and come up with their own contract items. This encourages each student to pursue a topic she is interested in. This also gives the teacher a chance to hear the student’s idea and help shape and improve the activity.

English Contract - Organizing by Open Work Time Sessions

(Thanks to Jen Krause of Niles West High School)

In this contract, the activities are broken into work to be chosen on any given open work time (OWT day). Each day has a particular skill or essential question to master, and each gives the student a choice between continuing to practice or to move on to an enrichment activity (“challenge”). In addition, for each activity, a student is asked to self-evaluate her effort, her understanding of the activity, and how well she collaborated with other students.

Organizing a contract in this way gives a teacher more flexibility in planning the calendar, since an OWT day can be scheduled at any time on an as-ready basis.

Geometry Contract - Test Remediation

(Thanks to Vanessa Brechtling of Niles West High School)

This contract was handed back to students with their graded tests. Since they are given the answers, they can see what they should have done and can take steps to learn from their mistakes. Each question they got wrong has a specific set of activities to do as remediation. If they got all the questions correct, they can move on to steps two and three—enrichment problems. Students who only had a few answers wrong can do the required work and then move on to steps two and three.

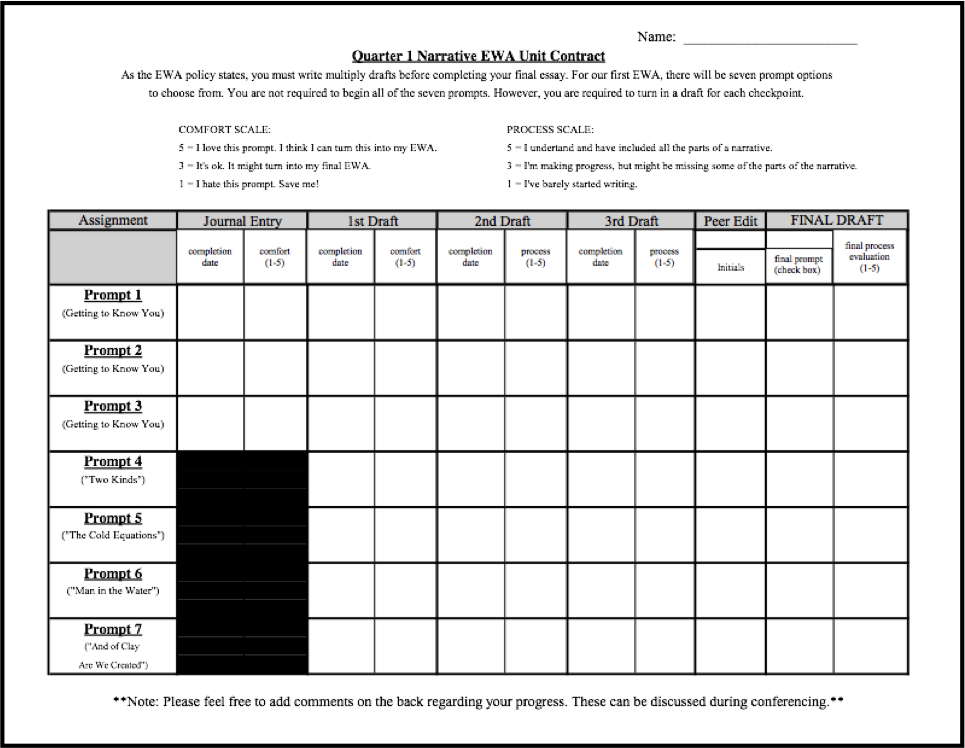

Writing Contract - Scaffolding for a Process

(Thanks to Amanda Lipinski and Patrick Noote of Palatine High School)

All of the above contracts are focused on student mastery of specific concepts and/or skills. There are, however, situations where the learning goals don’t fall into either of those categories. For instance, when a student is working on a long-term project or a creative effort, such as painting or writing, what is needed instead is a structure to guide students through the process.

This contract creates the scaffolding for a long-term writing assignment. Students begin by writing exploratory essays around one of three initial prompts or topics. For the first journal entry, students are asked to assess how comfortable they are with the topic. This helps guide them in deciding whether to continue revising that essay or to pursue a different topic. Before a first revision draft of that essay is due, they are allowed to move on to any one of six other prompts. After that stage, they are asked again how comfortable they are with the prompt and are allowed to shift to another one. By the due date of the second draft, it is assumed that they have landed on the topic they wish to pursue for the rest of the project, and from this point on, they are required to self-evaluate how well they are completing the process of revising their work. In this way, guidance is given both in choosing and in editing the essay. Finally, their work is peer edited and turned in to be evaluated.

Rolling Contracts - Fluid Differentiation

(Thanks to Sarah Dyson and Liz Sheehan of Palatine High School)

The contract below is simple but effective. The teachers in a reading and writing class came up with a way to provide guidance for their students during “extra time”—that is, time in which students have completed the assigned classwork for that day and are looking for something to do. The contract in this case is pasted to the wall and consists of two parts. The first, “Always an option”, is a list of activities the students can pursue no matter what the current topic is. The second, which is pasted onto the poster, describes those activities that are specific to the current unit of study that are available when a student finds the time to work on them.

6.6 Designing Minicontracts

6.6 Designing Minicontracts

While minicontracts can vary in size and complexity, the design always proceeds through a sequence of steps.

The first is to articulate what learning goal(s) are to be mastered. What should students know or be able to do when they have finished the contract? A contract may also be designed around a specific task, such as preparing for a test. In any case, the process is one of planning backwards from the purpose of the contract.

Several forms of feedback have to be created to determine 1) which contract items each student will do and 2) whether the student was successful in mastering the goals at the end of the contract. The use of feedback is explored in depth in “Grades Reconsidered”.

Often, existing materials such as homework assignments or classroom activities can be incorporated directly into the contract. Now, however, the full range of what students need has to be taken into account. New remedial work will often need to be created for the students who are struggling and enrichment activities created for the more successful students. Contract items may also allow for a range of learning styles.

In addition to differentiated work, more complex minicontracts may include essential items that are expected of every student. Defining an item as essential means that the teacher believes every student must do it in order to be proficient. For a student who learns more quickly, the essential work may be all that is needed to master the material, in which case she can move on to enrichment items. For the student who takes longer, however, the essential items are just the starting point of the learning process, and they will be followed by remediation items.

The logistics of how students do the work must also be determined. Are they working as individuals, in small groups, or in larger groups? Are some students participating in a teacher-directed workshop while others work independently? How much time will they have? Will they be able to take the work home if they don’t finish it in class?

Students should be aware of the expected outcome of the contract. Should they produce a product, like a completed worksheet or a short essay? Should the product be turned in for evaluation or kept in a portfolio as a record of their work? Should the follow-up feedback be evaluated for a grade or simply be informative?

Finally, will the contract itself be evaluated? If so, will the evaluation be done by the teacher or the student? In either case, the guidelines for contract evaluation should be explicit, clear, and as simple as possible. The topic of student self-evaluation will be treated in much more detail in the following chapter on unit contracts.

6.7 Other Considerations

6.7 Other Considerations

Adapting contracts to specific situations

The design of a contract may vary significantly depending on a number of factors. A Spanish class will need a different structure than an Algebra or a U.S. History class. Contracts for high school freshmen will likely need more constraints than those designed for seniors.

Another design factor is the variability of student readiness and motivation to learn. When faced with a wider range, teachers may have more difficulty providing the appropriate level of challenge for every student. By design, the "detracked" courses have a dramatically increased range of abilities. In this case, more flexibility must be built into the contract to accommodate the needs of all the students.

No matter the situation, however, the goal is to have every student learning optimally by working at the appropriate level of challenge at all times.

Evolving from teacher-directed to student-directed choice

Contracts can be introduced with limited or no choice on the part of students, but one of the principle goals of this structure is to wean students off their dependence on teachers and help them take responsibility for their own learning process.

The graphic design of contracts

Regardless of the scope of a contract, its graphic layout should be as simple as possible. Excessive verbiage—complex instructions, rubrics, scheduling guidelines and the like—should be avoided. These are generally ineffective forms of communication, and they clutter up the central task of offering differentiated work to the student. The design should include lots of white space in the margins and between sections of the contract, and the font should not be so small as to make it look like a legal disclaimer on a credit card bill. The question of clean graphic design is discussed in more detail in the next chapter on unit contracts.

6.8 Introducing Learning Contracts to Students

6.8 Introducing Learning Contracts to Students

Student buy-in is essential

Students are much more likely to be engaged and motivated if they believe in the philosophy embedded in the contract system. Therefore, the way in which contracts are introduced is critical. Students must come to believe in the value of differentiated learning. The contract system is designed to eliminate busywork and give additional time to students who need it. Most students understand and appreciate the contrast between this and the traditional once-size-fits all approach found in most classrooms. Many will embrace the goals of eliminating the bell curve of grades and providing every student with an appropriate level of challenge, particularly when they understand that they will have voice in deciding that level.

Student beliefs must be addressed

Built into the very fabric of contracts is the idea that all students can be successful through effective effort. Many students, however, believe that grades are a measure of intelligence, and that if they are failing, little can be done about it. This fixed mindset is a major impediment to effective effort, since it precludes learning from mistakes and shuts down the learning process prematurely.

Furthermore, students who struggle in school often feel shame or anger when they get their grades. They take failure personally and act out or withdraw. Poor test scores become a depressing reminder of that sense of failing and being a failure. Given this, it is hard for them to see grades as useful feedback or to believe that they can learn from their mistakes.

A discussion about learning in the comfort zone (as described in the last chapter) can help students understand the basics of differentiated learning. This presentation needs to be adapted to the students’ maturity and readiness to hear it, of course, but it will often lend itself to an interesting discussion. In particular, a nonjudgmental discussion about the different ways and rates at which students learn is an important step to begin redefining mistakes and seeing failure as feedback.

Training students in self-awareness

Differentiation in contracts may be designed around activities that are effective for different learning styles. Students can simply be given a free choice between visual, auditory, and tactile-kinesthetic activities, of course, but they will become much more effective in making those choices if they are aware of their dominant learning mode.

Starting small

For the sake of your students as well as yourself, it is advisable to make the first contracts limited in scope. Since the very idea of differentiated activities may be alien to many students, starting with a simple choice is a good first step. A minicontract can offer a branching of student work into two activities. This might be used for a short, in-class follow-up to a homework assignment where some students have mastered a new skill and some haven’t.

As your students (and you) become more comfortable with the idea of individualizing the learning process, the contracts can grow in complexity and scope, eventually leading to the use of unit contracts, described in full in the next chapter.

Preparing students for making effective choices

Some students may find it shocking that they are expected to play an active role in the learning process. On a basic level, many students, even successful ones, are often unprepared to make good choices. They may never have had the experience of making an independent decision about learning. Even if they have, they may be driven by inappropriate or counterproductive motivations. “Good” students are often preoccupied with what they need to do to get a good grade. In focussing on what the teacher is expecting of them, they may not even be conscious of what they need to do to learn effectively. They may also choose to do busywork that they can complete easily and quickly so as to save time for other work they have to do for other classes. “Bad” students, on the other hand, may choose work that is not challenging enough so that they can avoid being embarrassed by failure of any kind.

Making responsible choices is a skill many students will need to learn by trial and error. They may not be particularly good at it at first, and will need guidance and extensive feedback from you. Therefore, it is essential for you to have patience, while remaining firm in your commitment to differentiated learning.

Teaching students the difference between freedom and license

Since most students’ experiences in school are highly controlled by their teachers, they are likely to confuse not being told what to do with not needing to do anything at all. The idea that they would choose to work when they “don’t have to” will be a novel experience for many. The ability of students to act responsibly as they learn is the very heart of being self-directed; the importance of their understanding that fact cannot be overstated.

Teaching students self-evaluation

Although it isn’t necessary to include self-evaluation in the first few contracts, ultimately students should be given this responsibility. Whenever they first begin to evaluate their own work, they must be given support and feedback so that they can internalize the ability to discern excellent work and strive for it.

It is important to remember that students may have no experience in actually determining for themselves how well they are doing. Having them learn this important skill takes patience and persistence.

6.9 Feedback and Learning Contracts

6.9 Feedback and Learning Contracts

Feedback steers the learning process

At the heart of the contract system is the task of making well-informed, effective choices that optimize learning. In order to be well-informed, students must have good and frequent feedback. Feedback makes learning visible to both student and teacher and affects the behavior of both.

Feedback refines the design of the contract

By paying close attention to what contract items students need in order to learn the material successfully and completely, teachers can make their contracts more effective over time. For instance, if students are learning a complex skill, feedback can be designed to expose the difficulties they are having with specific subskills. Such feedback may help students discover that there is a particular aspect of the material that they need to practice further. If you are paying close attention, these needs become apparent and can lead to the creation of a new contract item addressing that particular issue.

Feedback provides closure

Whether you are using a minicontract for students to prepare for a test or a unit contract (as described in the next chapter), feedback can tell you whether it is time to wrap up the current work or whether students need more time. Without such feedback, you might move on and leave holes in some students’ understanding that will haunt them in later units. Of course, tests themselves can be seen as feedback, particularly if they are designed to be formative. If a student can continue to learn from her mistakes on a test, then the test becomes part of the learning process, rather than the end. Students who did well can move on, and students who are struggling can continue to work on what they didn’t understand while simultaneously addressing the next topic.

Feedback and the evolution of learning contracts

Students are not the only ones who need feedback. Regardless of scope, your first contracts will improve much more quickly if you are open to feedback and constructive criticism from your students. Since the purpose of contracts is to be responsive to students’ needs, it is important to listen to them. When students understand that you consider their voice important in developing the use of contracts, it gives them a sense of power that they may never have experienced before in school.

Open work time is the most fluid aspect of contract structure, and it is the most amenable to a flexible attitude. By interacting with your students as they work, you can get a good sense of how they are doing with the material. You can determine whether the amount of time set aside for open work is too little or too much and can adjust accordingly.

Finally, open work time is an opportunity for you to model creativity and flexibility as a teacher. If you try a new strategy that doesn’t work as you planned, you can show students how important it is to learn from mistakes and correct them. For many students, the idea of a teacher intentionally "trying" something without being certain of its success is novel, to say the least. Such vulnerability can dramatically improve the working relationship between teacher and student.

6.10 Fairness

6.10 Fairness

Learning contracts and grades

Any set of differentiated activities must include work that is challenging for the most advanced students, and this kind of work immediately raises questions of fairness in grading. Why should a student take on additional challenges if she is not going to be rewarded with higher grades? How can there be a fair grading system if some students are doing more sophisticated work than others? The contract structure challenges the motivation many students have for doing schoolwork.

If learning goals are designed with the intention of every student being able to master them, (the definition of standards), how do we encourage students capable of more depth and sophistication to take on work that is challenging enough for them? The next two paragraphs describe two ways to think about this problem.

Above and beyond

One way to deal with the issue of standards is to define the essential learning goals for any given contract such that every student, given a realistic amount of effort, can be successful in mastering them. All too often, lip service is paid to this goal, when in reality some of a unit’s learning goals are simply beyond the reach of all students. When that happens, they should no longer be called standards; they should be redefined as aspirational goals.

For students who achieve the learning goals quickly, contracts should make more sophisticated work available, with the proviso that their understanding of that material will not affect their grade. Such work is "above and beyond" the standards that every student is expected to master. It exists so that every student is challenged appropriately and busywork is replaced with meaningful work. The idea that students would volunteer to do challenging work without a grade incentive may seem overly idealistic to teachers and students who haven’t experienced it. It is, in fact, a quite normal and ordinary experience when the appropriate classroom culture is established. This idea of “above and beyond” work is explored more fully in the last chapter.

“Honors” credit

Many schools are working to detrack their course offerings. Students who were previously in separate courses (called honors, regular, and general, for instance) are now together in one class. While detracking can have a number of important benefits, it also creates new problems. For instance, tracking structures often included a grade point bonus as an incentive for successful students to take honors level courses. When courses are detracked, one way to deal with the loss of that bonus is to allow students to earn “honors credit” by doing additional work, above and beyond the required curriculum. Contracts lend themselves to this approach quite effectively. Simply renaming “above and beyond” or “enrichment” items on the contract as “honors” work ensures a definition of who should receive honors credit.

While a student’s mastery of "above and beyond" learning goals may or may not be assessed by the teacher, “honors credit” goals should be tested in order to determine whether students have, in fact mastered the “honors” level work.

6.11 Learning Contracts and Grading

6.11 Learning Contracts and Grading

The grading of contracts

If classwork and homework are being graded, the use of learning contracts can organize those grades more efficiently. A minicontract, with a choice between several activities, can be graded in exactly the same way that any comparable work would have been graded if there were no differentiation. Multiple contract activities in a minicontract can be entered into the grade book as a single entry and weighted based on the number of items completed. This reduces the bookkeeping associated with classwork and homework.

Contracts are a record of the learning process

Whatever form of learning contracts or grading scheme you are using, contracts can help document the learning process and make grading more accurate. By having clear and explicit guidelines for assessing each contract item and the contract as a whole, evaluating the learning process is more fair and transparent.

Contracts and student self-evaluation

If student self-evaluation is a part of contracts, it deconstructs students’ dependence on rewards from teachers and helps them internalize their motivation. It also requires them to internalize the notion of excellence and to view their own work through that lens. In addition, it frees up teachers to give more subtle and meaningful feedback through different means, such as one-on-one conversations.

Contracts and grade conferences

Regardless of their scope, contracts can become a written record of student work that can be viewed and discussed in grade conferences at the end of each marking period. Laying out contracts on a table and looking at the accumulated evidence of the learning process can lead to powerful and meaningful conversations.

6.12 Tenets of a New Paradigm

6.12 Tenets of a New Paradigm

Learning contracts make authentic student choice possible

They can be used to teach students the qualities of self-directedness and personal responsibility.

Student ownership boosts motivation

The freedom to make choices and steer one’s own learning stimulates the internal motivation to master the material. The drive to accumulate points and high grades is displaced by the desire to become better at learning.

Boredom is a choice

For many students, boredom is a regular feature of school. Students commonly blame teachers when they are bored because they have been assigned busywork. Learning contracts eliminate this problem. When a student has chosen to do work that is repetitious or too easy, it’s no longer possible to blame the teacher: it is a bad choice, no more, no less. Discovering that boredom is no longer required or necessary undoes a common source of student resentment.

When a student steers her own learning process, she learns more, both about the curriculum and about herself as a learner

Because she can learn to pay attention to what she needs and to make good choices, she can become much more effective at learning. And at the same time, she is learning to become more a responsible and self-directed individual.