Whenever practicable, have students evaluate themselves.

Take a good look at everything that you now have grades for, and ask whether it is truly essential that you do the grading for all of them. The balance between student and teacher evaluations will depend, as always, on the maturity and readiness of your students, but also on your own personality. Allowing students to self-evaluate gives them some of the power you once had. Seen from this point of view, it reduces your leverage in affecting their behavior. Nevertheless, when looked at candidly, there is often no compelling reason to block students from evaluating their own work. The loss in leverage is generally more than offset by gains in student motivation and ownership of the learning process.

The frequency with which students need to turn in their work for your direct evaluation is determined by how often they need your written feedback, as opposed to discussing their work in person or having their study group giving them feedback. Depending on the nature of the work, written feedback might need to occur daily, or as rarely as once per contract. It will probably be more frequent at the beginning of the year when you are still establishing the standards of excellence, and less important later, when students have learned to be better at self-evaluation and study groups, and other support structures have become more effective in supplementing your feedback.

Make timeliness part of the evaluation, if it is appropriate.

Some student work has a hard deadline, and the work will be more valuable in the learning process when it is done on time. For instance, if students must complete their homework in time to participate in a study group conversation, the deadline is not flexible. Doing the work and being ready for the discussion makes it a much more valuable learning experience than showing up cold. Therefore, any self-evaluation of late work should reflect that the work is now less valuable.

One way to distinguish work that has been done on time from that which hasn’t is to use a stamp. (If the work is done digitally, it may be more of a challenge to find a suitable marker for timeliness.) Here are a few ideas about how to think about and implement their use:

Receiving a stamp can legitimately be part of the value of the homework. My students, for instance, evaluated how well they did the homework process on a 1 to 5 scale, as seen below, where a “5” meant excellent work and a “1” meant a minimal effort. Work that was completed after the deadline (and therefore did not receive a stamp) would be rated a maximum of “3”, meaning it was a mediocre effort. A stamp should be a prerequisite for excellent work.

The stamp serves a number of functions. It marks the transition between the individual effort and the conversational learning that follows. The stamp is an easy, clear record of how often students make deadlines or complete homework, which can be useful in helping students with procrastination issues or other impediments to completing work. It is also surprisingly effective in motivating students to do homework. It can boost the peer pressure — if everyone but one person gets a stamp, there is a sense of the one who didn’t do it having let the group down. This can be amplified by giving everyone in the group a “double stamp” if they all receive a stamp. This doesn’t have to be “extra credit” — in my experience, it works remarkably well as a strictly symbolic gesture.

While it may be useful to stamp their work with a date stamp, there are several disadvantages; they are readily available and can therefore be easily faked, and they are unimaginative and utilitarian. Using a playful stamp is a way of injecting fun into the process. It is worthwhile to accumulate a collection of stamps over time and vary them as you see fit.

The role stamping work can have in boosting responsible behavior, not to mention increasing homework completion, is described in detail in “The Role of Student Work”.

Teach students to be honest, skilled self-evaluators.

Training a student to evaluate herself accurately and honestly is essential, particularly at the start of the year. A student may or may not have the metacognitive ability required to assess her own work, but this is an important skill for her to develop, and one that makes her learning process much more effective.

It is important to begin by teaching students to evaluate one aspect of their work at a time. I would have my students evaluate reading homework first and give them intensive feedback until they were largely self-sufficient. Then I would have them self-evaluate their lab write-ups, followed by self-assessing their work on problem sets. Since each type of work has its own criteria for excellence, each form of self-evaluation should reflect that. Within each format, only those aspects that contribute to the work being excellent should be evaluated. If timeliness doesn’t matter, for instance, don’t have it be part of the evaluation. That means clearly articulating the difference between hard and soft deadlines.

The process of teaching students how to self-assess can be accelerated by using self-evaluation forms like the one below at the start of the year. This way, there can be direct, immediate feedback on how honestly and accurately students are self-assessing. These forms need to 1) define clearly and concisely what aspects of the work make it excellent and 2) have a simple scale of evaluation. Designing such a form well means that there will be less overhead for you in managing your feedback to your students, and you will be able to respond more promptly..

Here is a sample form my students used to self-evaluate their homework. The upper section describes the criteria of excellence for this type of work. The lower section defines a common-sense scale of assessment. When you are reviewing how a student used it, any aspects of their work that are missing or incomplete can be simply highlighted or circled on the form. This is more direct — and more likely to be read and understood by the student — than writing out long descriptions of the problem. By helping a student isolate the specific difficulty he is having with the self-evaluation process, you are cultivating her metacognitive skills. You are also providing a succinct explanation of why your evaluation was different than hers.

Placing the student’s and teacher’s grades side by side shows the level of agreement clearly. Disagreements between you and your student about the appropriate grade can lead to meaningful discussions with her about what she believes excellent work and excellent learning actually look like. These conversations can bring her basic beliefs about her own capabilities to light. Since these beliefs are often instrumental in blocking effective learning on her part (“I’m no good at math”), this can be a powerful moment of growth in self-awareness and self-reliance.

Using other students’ work as exemplars can also clarify what excellent work looks like and can allow a student to zero in on what aspects of her work need improving. However, showing other students’ work must be done carefully and non-judgmentally. The issue is not about comparing one student’s work to another’s; exemplars are merely tools to help clarify how to improve. It helps to show student work that is anonymous.

Trust, but verify.

Students need to know, especially when you are establishing the roles you and they will play in the classroom culture, that you are truly giving them power to assess themselves and that you trust them to be able to do this honestly. Many students will be skeptical and assume that it is an example of fake responsibility or a trap you have set for them. It may take time for them to accept the new classroom culture as genuine. It is essential that students understand that you intend to help them overcome their misguided and counterproductive desire to accumulate points. Together, you will replace that desire with the ability to appraise and steer their own learning more effectively and honestly.

Mutual trust is the cornerstone of the classroom structure. It must also be clear to students from the beginning that they can abuse that trust, but that if they do, they are losing something important. It is the fear of losing your trust in them, not the fear of being punished, that will ultimately allow them to see that cheating is self-destructive behavior.

Part of establishing this culture and your working relationship with your students is to convince them that self-reliance and honest self-assessment are important life skills that you will help them learn, if they don’t have these skills already. Many students will quickly (and often enthusiastically) take ownership of the process of self-assessment. For those who struggle with it, the struggle can lead directly to conversations which may be more important and meaningful in their lives than any of the content that they may learn in your course.

A typical opportunity to direct a student towards honest self-assessment occurs when her results on tests are much poorer than her reported evaluation of her homework covering the same material. Diagnosing why this discrepancy happened together with the student helps clarify the usefulness of honest self-assessment. If she knowingly boosted her homework assessment order to get a better grade and avoid doing needed additional practice, the direct result that she was unprepared for the test. That’s clearly not in her self-interest. If she did badly on the test due to test anxieties, despite having mastered the homework, that is a specific challenge that needs to be addressed separately. If she was surprised by her poor test grade (“I thought I knew it”) that is a different problem: She was simply not conscious of the aspects of the homework that she hadn’t yet mastered. That means that she needs training in paying attention to the signals that indicate she still requires more practice. In other words, honest self-assessment is in her best interest.

Keep it simple.

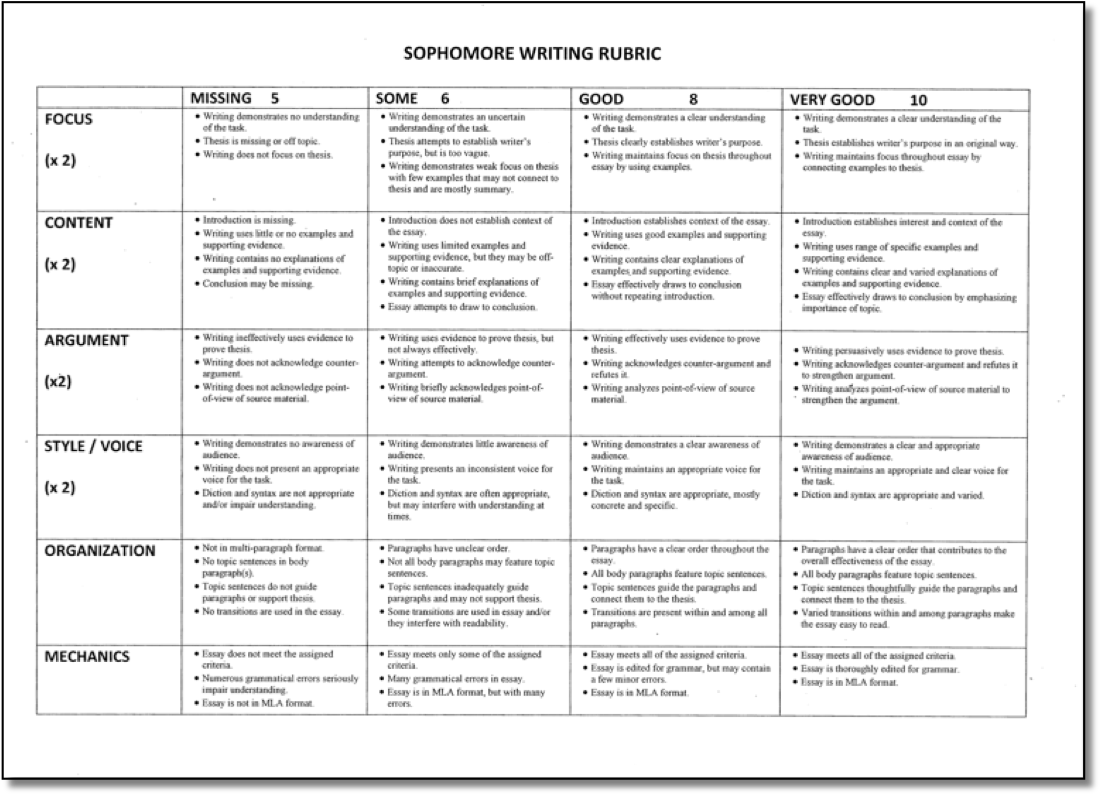

Students need a structure to direct their self-evaluations: a way of defining what excellent work looks like and what is missing when it isn’t excellent. This often takes the form of a rubric. Unfortunately, such guidelines are often complex grids, using language that is alien to many students. Here is an example of a student unfriendly self-evaluation form.

If the purpose of self-evaluation is to cultivate metacognition, then the structures we give students must not be forbidding and off-putting. One of the central tenets of effective communication is to speak to students in their own language. Even though it may be useful for you to have learning goals defined in great detail using language that you understand as a teacher, such language will be a barrier for students, particularly those who are immature or academically unsuccessful. What students see should be as simple and direct as possible. If it can be expressed in 10 words, don’t use 13.

The complex grid shown in the matrix format can be completely replaced by the form below. Every aspect of the criterion for success, listed in the right hand column of the matrix, has been translated into language that is more accessible to students. Yet it still gives the teacher the ability to give specific feedback on aspects that need work. Notice that even the evaluation scale has been dramatically simplified and translated into language that any student can understand and use. (Thanks to Steve Wool of Evanston Township High School.)